The soil. Since we already covered the 51st parallel thing, we can go into the soil straight away.

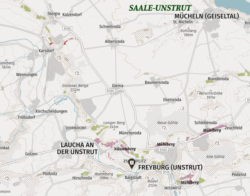

Muschelkalk, good old Triassic limestone, provides the general foundation for Saale-Unstrut, the viticultural area where the Saale and Unstrut rivers come together, about an hour southwest of Leipzig for you Bach fans. (If it’s too much to compare the Sylvaners of Konni & Evi with Chablis, as the latter is, in general, riper and plusher by far – to say nothing of the fact that Konni & Evi farm no Chardonnay – it perhaps explains the same chalkiness evident in the very different wines and regions.) There is also some loess and loam here too, and “Buntsandstein” or colored sandstone.

Saschen, or Saxony, is about two hours due east from here, and a touch further south, with Dresden as its center. The soils in Saschen are more granitic, with some loess and loam. The river Elbe flows through Dresden, in a north westerly direction, providing an orientating axis as well as a beneficial, southwestern exposure for the vineyards tucked along the river. The wine region is relatively concise here, extending as it does only about 30 miles, direction northwest away from Dresden.

Saschen, or Saxony, is about two hours due east from here, and a touch further south, with Dresden as its center. The soils in Saschen are more granitic, with some loess and loam. The river Elbe flows through Dresden, in a north westerly direction, providing an orientating axis as well as a beneficial, southwestern exposure for the vineyards tucked along the river. The wine region is relatively concise here, extending as it does only about 30 miles, direction northwest away from Dresden.

As all these soil types are oft-mentioned in the historical tomes of wine, it shouldn’t be too much of a surprise to learn that winemaking here goes back, far. The first written records of viticulture and wine were penned at some point in the late 900s.

There was a strong monastic culture here, in both regions, presumably doing the same mapping of terroir that they did in Burgundy and the Mosel. There are medieval carvings of vines and grape bunches in the old churches. In other words: viticulture was a big deal here back then. The medieval warming period you may have heard of in reference to other viticultural areas also helped Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen. Anne Krebiehl’s recent book, provocatively titled The Wines of Germany, states that there may have been up to 10,000 hectares under vines in medieval times.

I guess these ages weren’t so dark?

Today, there are about 800 hectares under vine in Saale-Unstrut. Saxony is reported to have just around 500 hectares. Even adding both these regions together, that’s still nothing. The Rheinhessen, Germany’s largest wine region, has nearly 27,000 hectares under vine, as a quick comparison.

If my math is right, Sachsen vies with the Hessische Bergstrasse (another German winemaking region you’ve likely never heard of, scattered just east of the Rheinhessen) for the nation’s smallest wine destination, though maybe only by a handful of hectares.

Interestingly, while the two regions are so far north (51st parallel ya hear?), the temperatures are not really that much cooler than they are in the cooler winemaking regions to the south. Sachsen does seem to be the slightly milder region, perhaps influenced by the larger Elbe river. Stephen Brooks, in his wildly overlooked 2003 book, provocatively titled The Wines of Germany, writes that the average temperature here is slightly higher than that of Trier (this is the city located closest to the Saar) or Würzberg (the major city and viticultural center of Franconia). Keep in mind that both of these places are quite cool viticultural areas and rest somewhere close to the 50th parallel. In truth, we’re not heading south so much as we’re heading west when we go from Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen to, say, Trier.

What is dramatically different is the severity of the winters – it is a “continental climate” as they say – and the shortness of the growing season. Thus, because of the harsh winters, vine death is a real issue. More critically, frost is a constant and very serious threat. The shortness of the growing season puts some very real constraints on the viticulture. In Saale-Unstrut, for example, there is almost no Riesling planted. Riesling is a late-ripening variety; in this extreme landscape only two vineyards seem able to ripen Riesling here, the Freyburger Schweigenberg and the Pforter Koeppelberg. (As a very exciting aside, we are hoping to work with Konni & Evi on a small bottling of Riesling from the highest parcel of the Schweigenberg!)

In Sachsen, spring arrives a bit earlier, and thus they have a slightly longer growing season. Riesling and the more noble varities are more common here including Traminer, Weissburgunder and Grauburgunder. Saale-Unstrut is the land of Müller-Thurgau; this is the most planted variety, followed by our beloved Sylvaner. There is Gutedel (Chasselas) and Portugieser. Grauburgunder is here too, and more and more Weissburgunder is being planted; it’s seen as being a bit foreign and exotic, you know, sophisticated.

You may have heard of Rotkäppchen? The word itself translates to “little red riding hood,” though in Germany it’s a famous, historic and ubiquitous brand of sparkling wines available in nearly all the grocery stores for only a few Euros. While today the company puts out thousands (millions?) of cases of tank-fermented sparkling wine (most of the juice trucked in from places unknown), it was founded in 1856 in Saale-Unstrut. From my limited research, the first wine school in Europe was founded in 1811 in Meissen, a small city just north and west of Dresden.

If you’re looking for really notable wine facts from the winemaking period after the medieval golden era, this may be all you get.

And while we Americans have a hard time really contextualizing anything, a wine culture or a cathedral, a thousand years old, the truth is there are old things all over Europe. So, while it’s cool and maybe surprising, that this northern region has such a deep history of viticulture, it’s not really that unique in Europe.

However, the events of the last few decades are unique, and perhaps more shocking, and perhaps more relevant.

In 1949, after World War II, both these regions, Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen, became part of East Germany, the GDR (in German it is referred to as the DDR). However, it’s important to note that the viticultural landscape here was already in bad shape even before the GDR began its unique form of industrialized viticultural oblivion. It had severely contracted because of the climatic cooling that took place after the medieval period, was hurt even further by the Reformation (destroying the work of the monastic cultures) and then devastated by phylloxera. It’s impossible, or at least very hard, to understand what the landscape really looked like, though it seems possible there may have been as little as “three dozen hectares” remaining in Saale-Unstrut, as Krebiehl reports, or perhaps closer to a hundred, certainly when you include Sachsen.

Regardless, however bad it was, it was bad. And the GDR made it worse. Whatever quality winemaking existed in these places was absorbed into the state-owned winery-machines, and thereby annihilated.

Or, is that just the easy narrative? The one told because it is undeniable and in-your-face when you look back in time. There are countless stories of the commercial homogenization of viticulture during these times.

Krebiehl tells of a winemaker in the region recalling one of the large state-owned cooperatives, presumably making wine from many, many hectares. He states, they produced only one wine, labelled simply: “Müller-Thurgau.” It reminds me of the famous Henry Ford quote, the excesses of socialism and capitalism finding themselves pushed into the same posture: “All customers can have a car painted any color that they want, so long as that color is black.”

In Saale-Unstrut during the GDR, you could have any wine you wanted, so long as that wine was Müller-Thurgau.

Brooks narrates the story of one of Sachsen’s more famous estates, Schloss Wackerbarth. “After the Russians arrived in 1945, the Schloss [castle] was used as a prison, and then converted into a Staatsweingut [a state-run cooperative]. The vineyards occupied 130ha but no winemaking, other than for a sparkling wine, was undertaken here. The property was run by an army of 300 employees that included a permanent dentist (it’s tempting to speculate that his services were required to repair the damage inflicted on the staff by the overacidic wines).”

Interestingly, when you look at hectares under vine, they appear to have actually grown during the GDR. The problem, both with the vines planted and the wines made, was not quantity, but quality.

The three decades following reunification have also been poorly documented, at least in English. Krebiehl references one winemaker who lived through the moment of reunification. She quotes him saying: “It was a gold-rush atmosphere. It was the zero hour. You had no administration, nothing. There were many compromises. It was chaotic. Notwithstanding that, we made wine. We evolved alongside the authorities.”

What this really means, I don’t think anyone knows.

Here’s another story, again regarding Schloss Wackerbarth, again told by Stephen Brooks: “After the collapse of the regime in 1989, the Schloss resume wine production, but the state was keen to find a private buyer, which it did in the late 1990s. A new team arrived at the estate two weeks before the 1999 harvest. The winemaker Jan Kux recalls: ‘We tried to make the existing estate workers understand the need for radical change, but they were reluctant. We encountered workers who had their own keys to the tanks, so that they could indulge in private tasting parties! So we fired the entire cellar staff, and essentially made the 1999 wines with the help of students. A lignite-burning central heating plant provided the energy for the entire property, and I was appalled to see that the lower vineyards close to the Schloss were covered with a film of soot. This of course block photosynthesis, and thus ripening. The whole places was a disaster area.”

Keep in mind this story is not told days or even months after reunification: this is nearly a decade after the wall fell. Brooks, writing in 2003, says of the wines from these regions, “Their wines were, and indeed still are, consumed locally for the most part. Before the 1990s opportunities to taste them were rare, and on the few occasions when they passed my lips, the experience was not memorable. Most of the wines were Muller-Thürgau at its most tart.”

And here we are, nearly 30 years post-reunification and Brooks’ quote is still largely true. The wines are still, for the most part, consumed locally. Occasions to taste them, certainly in the U.S., are rare. The remaining question, regarding their quality, how “memorable” they may or may not be, that’s the one that’s less easy to answer.

We are certainly no experts here, though we’ve been fascinated by the region for years. We’ve visited and walked the vineyards, put our hands in the soil. We’ve probably tasted more wines from this region than most (any?) other Americans, if not most other Germans. Though both these are both low bars, admittedly.

Of everything we’ve tasted, the wines of Konni & Evi were nothing less than a revelation. You can read more about them here.

Yet, for the historical record, what Konni & Evi offer is a glimpse of the less obvious narrative of this region. For the most part, Konni & Evi farm vines that are older than the GDR itself. Thus, the viticultural history they are nurturing has nothing to do with the industrial winemaking philosophies of the eastern bloc, unknown varieties planted up to (and beyond!) three meters apart (nearly 10 feet), to allow room for the largest of tractors to process the grapes. Konni & Evi’s vineyards, and verily their wines, reference a viticultural tradition before the GDR. Some of these vineyards are planted at incredibly high densities (10,000+ vines a hectare), most of them are terraced or planted in such steep areas that there is no option other than tough, inefficient, time-demanding, hand work.

And the fact they inherited these sites in some form, that the sites weren’t swallowed back up by nature, indicates that people were farming them, were perhaps even cherishing them and loving them, behind the wall. These people, regular farmers and villagers, preserved this culture and by doing that… saved it.

Most likely they did all this work in their spare time, early in the morning, after the day’s labors, on the weekend… on holidays. Perhaps the wines they made were not good, maybe they were great. The only thing we know is that they are unknown to us now.

Yet the vines, the vineyards, live on… and we can meet them again.

There is an amazing history here, and the future is being written in the present.