“For the sake of the cultural, social, environmental, and economic vitality of the entire region, Ulli Stein is calling for a concerted, widespread effort to save the remaining vines of the Mosel. He urges winemakers to pay above-market prices for the grapes purchased from steep sites and to seek out endangered vineyards; he encourages grape-growers to hold out in the face of downward pressure on prices; he suggests that aging winemakers relinquish their plots in alluvial soils along the river in favor of continuing to work the steep slate sites above it; and he solicits support from fellow Mosel residents in trumpeting the singularity of their region. None of these suggestions will succeed in isolation, and even with a coordinated effort, the forces aligned against wines of unique personality and uncompromising quality are well entrenched.”

“Still, as Stein says, it’s worth a try, if not for lovers of Mosel Riesling, then at least to honor the old Riesling vines themselves,

which have earned a chance to be protected from thorns.”

Published in The Art of Eating, 2010, No. 84

For nearly all of recorded human history, the Mosel has been a place of viticulture.

When the Romans were putting the limestone finishes on the Colosseum around A.D. 80, there were likely Romans in the Mosel, building walls out of slate to cultivate these cliff vineyards. The city of Trier — the main city of the Mosel and the oldest city in Germany (also the birthplace of Karl Marx) — was the northernmost outpost of the Roman empire; it was called Augusta Treverorum. It’s wild to consider, but Trier, in Roman times, was almost as big as it is today. Around A.D. 300, the population is estimated to have been 65,000 – these days it has grown to only around 100,000.

Today in the Mosel, you can’t spit without hitting a Roman press house or an abbey founded in the Middle Ages. Walk through any of the villages and you see markers over the doors of the timber-framed homes, casually declaring “erbaut 1560” — built in 1560. In the late 19th and early 20th century, as nearly any German wine importer will tell you, these were among the most expensive wines on earth, matching and in many cases bettering the prices of Bordeaux and Burgundy.

For many Americans, the fact is the Mosel is what we think about when we think about German wine.

It is a canonical place, one of the first regions the young wine student learns about, right along with Champagne, Bordeaux, Rioja, Tuscany, Piedmont. Many of Germany’s most famous vineyards are in the Mosel, with names both poetic and evocative: Sonnenuhr (sundial), Würzgarten (spice garden), Goldtröpfchen (little drops of gold), and Himmelreich (kingdom of heaven), to name but a few.

This Mosel River, with its extreme contortions and 180-degree hairpin turns, has shaped some of steepest and most dramatic vineyards in the world. At their most severe, these vineyards resemble fortresses; their sheer scale and verticality seems to transcend human ability.

The Mosel is a Stonehenge, magic and ancient and mysterious and improbable if not simply impossible. Yet there it is.

At the same time – and this is the stark reality I think few Americans realize – the Mosel is unquestionably

a poor place.

And right now, the Mosel is, in many villages, a dying place.

This is the jarring contrast, the discordant reality: The Mosel is both a mythical realm and a vanishing culture.

For wine lovers in Germany, in Europe, the Moselle is often seen as a bit provincial. A bit of a country mouse to the Rheingau, Rheinhessen, and Pfalz’s city mouse.

Drive through the famous towns in the Pfalz’s Mittelhaardt and you’ll see a traffic jam of large Audis, BMWs, and Mercedes lined up at rather fancy-looking estates. There are manicured lawns, maybe some fountains. The people visiting these estates have expensive-looking eyewear; their clothes have been recently pressed. With some rare exceptions, you do not see this caliber of eyewear or dry cleaning in the Moselle. Instead of big fancy cars, you see a lot of old and small Skodas and Opels; you see even more RVs.

This is another fact of the Moselle that I think Americans miss. For many Germans — for many Europeans at large — the Moselle is just a very long and winding campground. That is its main claim to fame.

For miles and miles along the Moselle, people sit on folded chairs in flat, grassy RV parks, the men shirtless, basking lazily in the sun. Above them, behind them, all around them are some of the greatest vineyards on earth. Few of these tourists seem to care much. For them, the vineyards are a nice backdrop to the peaceful river.

It’s a beautiful place, and it’s not expensive. That’s enough.

In other words, part of what makes the Moselle so complicated is the nose-in-the-air wine connoisseurship endorsed by goons like me, flanked by the crowds actually gathered there for sausages and water skiing.

It’d be something like having an amusement park right next to Vosne-Romanée, so that all those well-heeled visitors, recently deplaned from their private jets, had to take in the majesty of Romaneé-Conti within earshot of screaming kids, whiffs of cotton candy, and the sound of diesel generators.

The Moselle is this and more. It is unquestionably rustic, with small hotels and pensions that have rarely been updated over the last three or more decades. Summer here is the “high time” — your average Moselle winery probably sells most of its wine quite cheaply to these European tourists to help them wash down their döner kebab and currywurst – or just to take home to friends, souvenirs of time spent in “wine country.”

In the winter, the valley is empty. If this stillness is profound and refreshing for someone who’s lived in New York for over twenty years, it also speaks of a land without obvious opportunity.

This rawness, even crudeness, has certainly hurt the Moselle as a destination, and in turn the reputation (and understanding?) of its wines. Those suburban neighbors who “collect wine” and will tell you (over and over again) about their trip to Tuscany have never been to the Moselle and have likely never heard of it.

If this is a fact part of me treasures, both the authentic rawness and the fact my neighbors have never heard of the place, it has also hurt the Mosel.

To begin to understand the current-day reality of the Mosel one can look at the total reported hectares under vine (including the Mosel, Saar, and Ruwer) over the last twenty years (2004 to 2024). What one sees, quite clearly, is a decrease from 9,130 hectares to 8,440 hectares – a loss of 690 hectares. This comes out to around 35 hectares lost a year.

This in and of itself is neither inherently good nor bad. If we are being honest, the question is less a matter of total hectares – it is a question of what type of hectares: flatland? Steep?

Unfortunately, since World War II the Mosel has been moving in the wrong direction.

Consider that in 1950, in the era before the “mass production” of Mosel Riesling, the valley had just over 7,000 hectares of vines. Most of these vineyards were on the steep slopes, nearly all were terraced. By the end of the commercial corruption of Mosel Riesling, an era which saw the explosion of flatland vineyards planted to exploit mechanical production, regardless of quality, the Mosel had around 12,500 hectares under vine (1989) – a staggering growth of nearly 80% in only around four decades.

This growth, the expansion of vines into the flatlands once reserved for other agricultural products or livestock was in fact a critical part of the implosion of the reputation of German wine. We understand: More hectares aren’t necessarily good for the Mosel.

So, to really understand what is happening right now in the Mosel, we have to dig a bit deeper.

The unfortunate reality is that the growers are, by and large, not preserving the steep sites, the true cultural heritage of the Mosel. They are preserving the flatland sites, where by mechanical farming one can produce a wine able to compete in the world’s brutal economic market.

Additionally, not all villages and vineyards are suffering equally.

Drive through some of the most famous villages in the Mosel and things look alright – and I think they are, more or less. I’m talking about the Mittelmosel (Middle Mosel) villages from Piesport through Wintrich, Brauneberg, Bernkastel, Graach, Wehlen, Zeltingen, Urzig and Erden – the “Hollywood Mile” as I call it. Vineyard prices are more or less stable. These sites are farmed and the wines they produce can be sold at a profit.

Two key factors are at play. First, these are the famous villages with famous vineyards and a “built in” tourism. There is brand recognition here.

Second, and this is just as important, with certain exceptions most of the famous sites of the Mittelmosel are steep but smooth. In other words, they can be farmed mechanically. The Flübereinigung, or reorganization of the vineyards, carried out throughout the postwar period smoothed out the slopes of this part of the Moselle, like an iron being pressed to a wrinkled shirt.

Yes, these are the villages and the vineyards with fame, with commercial resonance; yet they can also be farmed mechanically, economically.

The situation changes when we move into the lower Mosel: the villages that run from Traben-Trarbach through Koblenz. The names of the towns here are, for the most part, known only to residents of the Mosel itself: Briedel, Zell, Alf, Bullay, St. Aldegund, Bremm, Valwig, Cochem, Klotten, Pommern, Müden, Burgen, Hatzenport, Oberfell, Niederfell, Gondorf – and even this is a highly edited list.

The few villages here that do have some resonance in the U.S. do so because of heroic growers (Vollenweider in Wolf, the Melsheimers in Reil, Clemens Busch in Pünderich, Stein and now Lardot and Curtin in St. Aldegund), heroic sites (the Bremmer Calmont, perhaps Europe’s steepest site), history (Zell’s Schwartzer Katz) or tourism (there is a famous castle in the village of Cochem).

Yet this part of the Mosel looks different as well; here the smooth hillsides of the “Hollywood Mile” are disrupted by jutting, oftentimes spectacular terraces, rising up like small angular monuments to an earlier version of the Mosel, which is in fact exactly what they are.

These terraces are a critical part of the identity of the Mosel.

Once you leave this “Hollywood Mile” of the middle Mosel, these most famous villages and vineyards, you also leave much of the tourism, you leave the hustle and bustle of the Mosel as well.

In the long span of the Moselle from Traben-Trarbach to Koblenz, over 30 miles long as the crow flies, everything changes. These are the villages and vineyards that are truly suffering. These are the sites that the Mosel may soon lose.

While advances in technology are designing machines that can mechanize the work in steeper and steeper vineyards, there are no machines that can work the terraces. Only humans can work the terraces.

What happens to a landscape when no one can or wants to pay for human labor?

There can be no doubt: These terraces are a great liability because of the extreme amount of human labor they require.

Yet we cannot forget they are also a great asset.

Because the terraces here were not disturbed, neither were the vines. The magic of this part of the Mosel is not only the terraces, but the old vines, the genetic cultural heritage that is here. Tiny islands of ungrafted vines 50 to 100 years old and older are commonplace here. Growers will nonchalantly speak of parcels planted near the turn of the (last) century; they raise their eyebrows and laugh gently to themselves when they see “Vieilles Vignes” declared at 30 or 40 years. In this part of the Moselle, these are adolescents hardly even worth considering; they go into the most basic cuvées.

Yet there is more at stake here than the growers’ “old vine” bragging rights. If 99% of the vines of Europe are on American rootstock, the Moselle is one of the few places where this pre-phyloxera heritage remains, somewhat unscathed. Can you taste the difference? Certainly the depth and complexity of old vines is unquestionable; whether the ungrafted detail is discernible I can’t honestly say.

But for me the true importance of these old ungrafted vines rests not in any specific quality of the wines they produce, in the same way the importance of the Parthenon rests not in the specific quality of the marble or the incredible sophistication of the design. What is important is the history, our united human history, here and tangible for our present and our future. This is one of the greatest, rarest, and least-spoken-of treasures of the Moselle.

To me it is perhaps the most important.

This is the Mosel we must save.

Yet to make this a reality, we have to better communicate their cultural significance, their historical importance, the singular elegance of the wines made from these terraced slopes. We have to be prepared to pay more.

It is here, in this forgotten place, where we arrive at the work of Philip Lardot and Rosalie Curtin. They are among the most-important young growers farming this landscape of sacred, yet-abandoned, sites. While growers such as Clemens Busch and Ulli Stein are here farming, and therefore saving, the ancient terraces in this region as well, they do so largely in their hometowns.

Lardot and Curtin are outsiders. And as outsiders, they are taking on vineyards scattered across this endangered region – they have no hometown.

A new acquisition in the St. Aldegunder Himmelreich; ungrafted vines in steep terraces, many of which will need to be rebuilt. This is back-breaking work.

Philip and Rosalie are farming approximately five hectares comprised from no fewer than twenty-six individual parcels spread out over six villages, from Clemens Busch’s home village of Pünderich, to villages completely unknown to the American market such as Briedel and Neef, to the once-famous Zell, to Stein’s St. Aldegund and further downstream, to a village I had never heard of: Briedern.

Of their holdings, roughly one-third, or nearly two hectares are steep, terraced vineyards, many of which have ungrafted vines trained on single poles planted before the world wars. In these parcels, everything must be done by hand.

This is one part of the story; the story of saving the Mosel.

Yet there is another chapter as well: A story of redefining what the Mosel is, or can be.

To pigeonhole this new movement in the Mosel as simply a “natural wine” movement would be selling it short, if not blatantly misrepresenting it. The inspirations appear to me to be less the youthful rebellion of much natural wine, and more a considered and thoughtful approach to a region (the Mosel) and a grape (Riesling) both of which shape wines of very high acidity.

In order to sculpt this formidable acidity into something more balanced, growers such as Lardot and Curtin rely not on residual sugar (all their wines are bone dry) but on some degree of skin contact and a more extended élevage in smaller barrels.

If this feels like a “new Mosel,” it’s important to remember two things: First, while Lardot and Curtin do work with Müller-Thurgau, Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris, their greatest holdings are of Riesling and their top wines are nothing more than single-vineyard Rieslings. In a certain way, the estate could not be more traditional. Second, it’s also important to realize that in some ways this new style of Mosel winemaking may have echoes from the famously dry Mosel wines of the late 19th century. This was, after all, a period long before filters and the ability to block malolactic conversions.

I had a conversation with Vinous’ David Schildknecht about this idea and he pointed out the following. In so far as growers like Lardot and Curtin recognize and value sélection massale (which most certainly they do in this old-vine part of the Mosel), in so far as they follow viticultural regimens less influenced by the technologies of the 20th century, in so far as they have a rather relaxed attitude toward malolactic conversions and value the delicacy and lightness of the Mosel, all of these characteristics would be applicable to the fin-de-siecle Mosel.

Yet, while a longer élevage could be seen as a throwback to a more “traditional” winemaking, in the late 19th century of Mosel wines, most of these wines were actually bottled quite early. Relying on spontaneous fermentation could also be seen as a “traditional” way of winemaking, yet Schildknecht pointed out to me that cultured yeasts were already in widespread use by the late 19th century in certain parts of the Mosel.

In the end my point is less that this “new” style of Mosel winemaking is exactly like it was 100+ years ago. While I don’t think it’s unreasonable to speculate that some of Lardot and Curtin’s wines may taste more like the wines made in the Mosel 150 years ago than do the contemporary Prädikat (off-dry) wines of many famous estates, this isn’t really my point either.

My point is more that culture is alive, that tradition is not static and is always evolving, changing, right under our noses. I strongly believe this style of winemaking in the Mosel has a powerful precedent and an influential future ahead of it. This is the authentic avant-garde.

There is no question to me that these outsiders, farming these forgotten old vines in the poorest and least-known villages of the Mosel, working the terraces and dedicating themselves to this beautiful yet financially difficult existence, they are the cavalry the Mosel needs so desperately right now.

But they also need help, desperately. Even in good times, the labor of the Mosel is extreme; the prices demanded by the market simply unreasonable. We are at a crossroads, with two futures in view. In the dystopian future, we ask the growers to subsidize this culture, these wines, through their own poverty, selling wines for ten dollars that cost them twelve to produce. This is unsustainable; eventually, they will stop. The other possibility is that we support them, that we scream from the rooftops about this sacred place, our common collective history, and we preserve it, by paying more. There can be no other way. What should we value more than human labor?

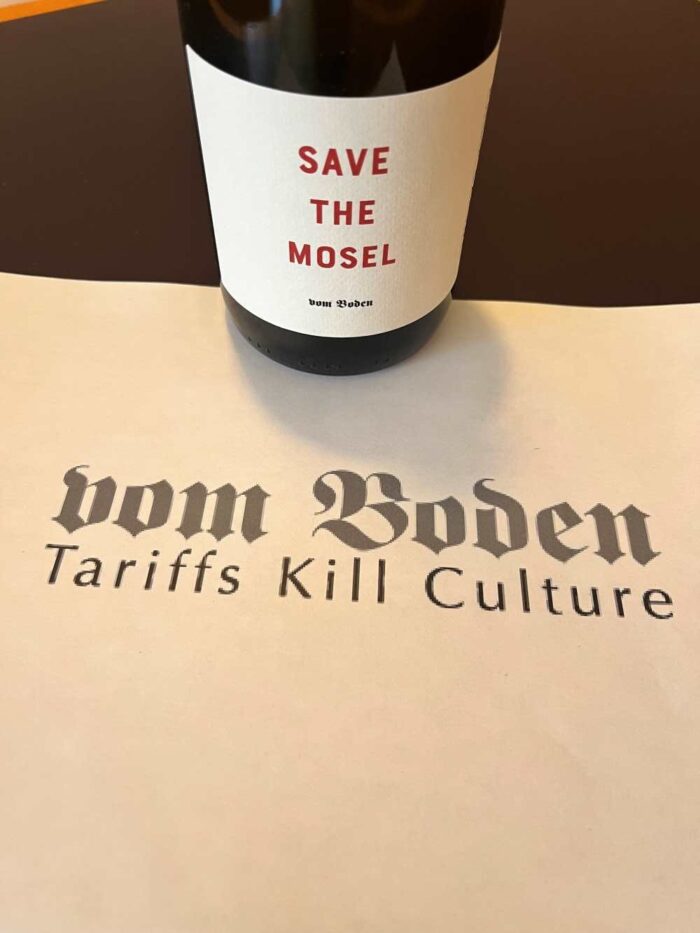

Our role, in short, is to SAVE THE MOSEL, to support Lardot and Curtin and the growers working the steep slopes of the Mosel, if not, as Stein said, for the lovers of the Mosel, “then at least to honor the old Rieslings vines themselves, which have earned a chance to be protected from thorns.