I first tasted Lukas’ wines in the summer of 2020, during the height of the pandemic lockdown. While I had heard about him – and thus kindly asked for samples as European travel was not really feasible – the wines came amidst an onslaught of samples, cases and cases shipped to me to taste, all alone in my kitchen.

It was exhausting; it felt like an unending army of bottles. Most were tasted, normally over a day or two, but then quickly disposed and forgotten. This is the business, alas. You have to taste hundreds of wines to find a few that really speak to you. Lukas Hammelmann’s wines, on first sip, made me take notice.

To be honest, I was blown away. I made it a priority to visit Lukas the first trip I could make to Europe in the late summer of 2021.

The Rieslings are absolutely screeching and blaze across the palate with raw citrus, green herbs and a bone-chilling acidity (more than one taster has confused Hammelmann’s wines with the Mosel or Rheinhessen, both in general much cooler regions than the Pfalz). These wines rip.

The Rieslings are absolutely screeching and blaze across the palate with raw citrus, green herbs and a bone-chilling acidity (more than one taster has confused Hammelmann’s wines with the Mosel or Rheinhessen, both in general much cooler regions than the Pfalz). These wines rip.

They are ruthless and in the first months as I tasted them they reminded me quite a bit of Schäfer-Fröhlich, though Hammelmann’s wines are perhaps punchier, more rustic and raw. While Hammelmann direct-presses, preserving the fierce acidities, most of the wines are aged in oak barrels, many of which are on the newer side. This is not an aesthetic choice – he’s not looking for oaked Rieslings – he simply wants very specific barrels and he wants to know the provenance. This one can only do with new barrels. Yet the combination of this ultra-high-toned fruit (raw citrus, lime zest, orange oils) and the subtle undercurrent of wood creates an effect that is minty and herbal. I find it incredibly appealing. Most of the Rieslings are bottled unfined and unfiltered so they can have a saline, leesy quality. I also find this incredibly appealing.

Hammelmann’s Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs (which account for only about 25% of his production) are more plush, more textural, yet they have a similar architecture, a certain force and rigor.

I have to say, now, three years later, having tasted nearly all of his wines from 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023, I am just as startled, just as invigorated, just as blown away and even more confident than I was years ago that Lukas is a rare and blazing talent.

I am confident that these wines not only show a new way forward for the Pfalz, but that they in fact present a provocative counter-narrative to what the Pfalz is, or at least how it is perceived.

It is time to tell his story, to dig a bit deeper. Let me explain.

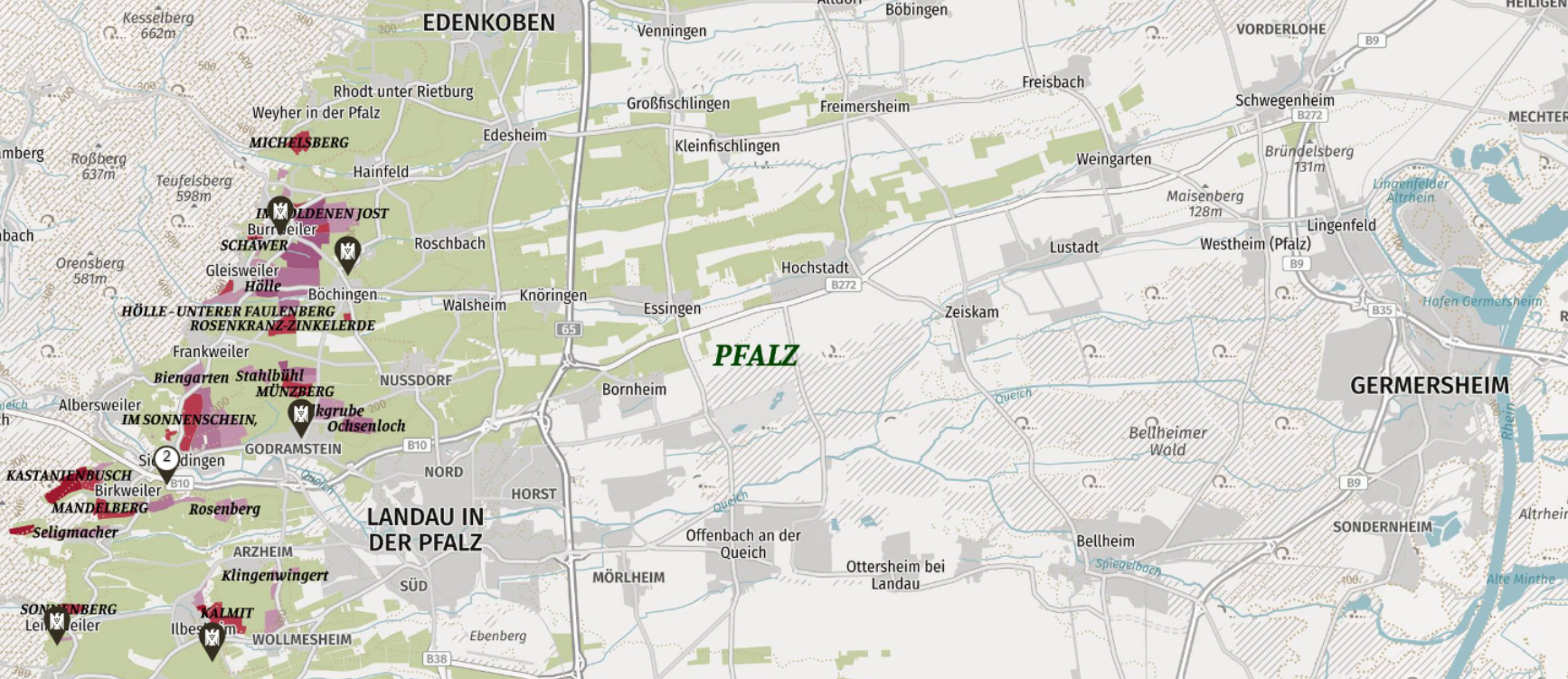

Lukas farms what can only be described as the cool (or cold?) flatlands of the Rhein basin; his home village of Zeiskam can be seen to the right of the green “PFALZ” label in the center of the map below. You’ll also note, no doubt, that all the “famous” sites are to the west, up into the Haardt mountains – all those purple and red squares. In fact, not only are there no vineyards of note even close to Zeiskam, the area isn’t even highlighted green. The VDP map shows it all as a part of that unpleasant industrial gray; it doesn’t even look like there’s a damn green lawn in the town. (Point of fact: There are many green lawns in the town, I have been there.)

Historically, apparently, Zeiskam was nothing; so cold above-ground it was only good for things that grew underground, potatoes and onions.

For the “good wine” you had to go twenty minutes west, to Rebholz’s south-facing sites, warmer and sheltered in the Haardt hills. Or, better yet, for that aristocratic juice you had to drive a half-hour north to the famed “Mittelhaardt,” to the towns of Bad Dürkheim, Forst and Deidesheim.

For the American wine visitor, I think the stature of the middle Pfalz within Germany is a bit lost or misunderstood, with its wealth and pomp. The central Pfalz, what the Germans call the Mittelhaardt, is something like the Germanic Napa Valley. Here you find the grand estates and manicured lawns and shiny cars driven by people with expensive taste in eyewear. There are a lot of “vons” here, which is to say lots of aristocrats. For a German, the middle Pfalz is fancy and when you come from the poorer Mosel, or even from the periphery of the Pfalz itself, there is something of a divide. The Mittelhaardt is for wines of breed and distinction and Zeiskam is for potatoes and onions. These are just lines you don’t cross.

Until someone like Lukas Hammelmann comes along and says something like: “Fuck you, line.”

And now we are at our counter narrative.

Not only is great wine not exclusively made in the blue chip zip codes, but there is a growing wealth of sites far beyond the famous Mittelhaardt.

How do we understand all this?

How do we understand all this?

In many ways, it makes no sense.

Yet in other ways it makes perfect sense. Lukas has said these site, these two neighboring villages (his hometown of Zeiskam and then Hochstadt, directly west) were historically too cool for great viticulture. We’ll discuss the confusing microclimates in a bit, but this is a trend we’re seeing all over the world: sites once too cold are now in the zone.

That said, I do think that for Hammelmann there are two other factors at play, both of them entwined within the other: determination and originality.

First, Lukas is just something of a force. I don’t think he’d have been able to accomplish what he has accomplished without just willing it to be. Even the way he speaks; he says things he believes as if they are a well-known fact that you should have already known. He believes Zeiskam was overlooked and ridiculed by people. He believes the terroir could be great… and now somehow it is.

Second, originality: In many places in Germany (or any old and famous winemaking culture) there is the tendency to copy, to emulate. I don’t mean this in a pejorative sense: oftentimes such copying is a reflection of a belief in a Platonic ideal. Hammelmann, for better or worse, is so completely on his own path that reference points for the first-time taster are hard. As I mentioned, there is something of the force of Schäfer-Fröhlich (who Hammelmann very much likes), something of the glaze and power of a more traditional Pfalz winery (say of Rebholz or of Christmann), yet also something of the acid-as-everything philosophy of a Weiser-Künstler or a Jonas Dostert.

The wines see extended lees contact and are normally bottled unfined and unfiltered with lower levels of sulfur, so there can also be something of a natural-wine aesthetic, though this is not to imply that they are not crystal clear.

In short, the wines are totally unique.

For me personally, after nearly two decades of scouring Germany, stops this fascinatingly new and complex and beautiful and thrilling are not all that easy to find. And when you find them, you stop and pay attention.

So that’s the contextual introduction; here are some basic facts, a little biography, some information as to what Lukas is growing and where.

Lukas always knew he wanted to make wine. He started studying wine as soon as he could and then took apprenticeships at various estates in the area. In 2016 he began his own estate with only a few small parcels around Zeiskam. Currently Lukas farms only around four hectares. He has said five hectares is about the maximum he would ever farm. Right now, overall, Lukas is farming about 70% Riesling, 20% Pinot Noir and 10% Chardonnay.

The VDP map above shows a cross-section of the lower Pfalz, running from the Haardt mountains (more like big hills) on the west (the left), down through the gradual slope toward the Rhine river basin on the east. Lukas’ hometown of Zeiskam is roughly in the center; directly to the west of Zeiskam is the village of Hochstadt. These are the two main villages in which Lukas farms. There is a third village – Neustadt/Hambach – in which Lukas has a few vineyards. Neustadt/Hambach is north and west of Zeiskam, just beyond the border of the map above. As with Rebholz’s village of Siebeldingen, the vineyards of Neudstadt/Hambach are in the foothills of the Haardt mountains. But we will discuss this later.

Zeiskam and Hochstadt are right next to each other and, overall, quite similar. The vineyards of both of these villages are in the lowlands, very exposed to the cool winds and much cooler in fact than the sites to the west and in the foothills. The western sites in the foothills often have more beneficial southern exposures and are sheltered from the winds, making them quite warm in comparison. This explains, at least in parts, the reason why historically these sites were more prominent than the vineyards in the lowlands and why the VDP map awards much greater prestige to the vineyards of the western parts. That’s why we have all those damn purple and red squares on the left side of the map.

As for size and soils, Zeiskam is smaller than Hochstadt, with only about 75 hectares under vine. Most of the famous villages in the Pfalz have 400+ hectares of vineyards, as a reference. The soils in Zeiskam are sandstone, loam and loess. Lukas farms around 1.5 hectares in Zeiskam; nearly all of it is Riesling. They have replanted some of it; most of the vines are around 15-20 years old. The only single-vineyard they bottle from Zeiskam is the Klostergarten and it is a Riesling.

Hochstadt is very similar to Zeiskam as far as the microclimate. It is a larger village with a few hundred hectare under vine. Lukas has roughly the same amount of vines here (about 1.5 hectares), yet because there is more limestone here and less sandstone, there are more Burgundian varieties including Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. The vine-age here is slightly older at around 20+ years. The only single-vineyard bottling from Hochstadt is the Roter Berg. Hammelmann bottles a Riesling, Chardonnay and a Pinot Noir from this site.

The soils, says Lukas, make a big difference. The wines of Zeiskam tend to have more structure and coolness; the wines of Hochstadt are stronger and saltier, but they usually also have more fruit and are more accessible younger. This, more or less, jives with my experience over the past few years, for what that’s worth.

Finally, Lukas farms less than one hectare in Neustadt/Hambach, a village maybe 20 minutes north and in the foothills of the Haardt mountains. If Hammelmann presents something of a counter-narrative to what one might expect from the Pfalz, keep in mind Hammelmann is in no way a rebel without a cause, or even much of a rebel, truth be told. Lukas in fact is a very serious and sensitive scholar of the history of the Pfalz with a tremendous pride in the region’s history and lore. The sites Lukas farms around Neustadt and Hambach are old and famous sites of the Pfalz.

The soils here are mainly red and yellow sandstone. There is no “village-level” wine made here, only three single-vineyards: a Schlossberg, Schlossberg Terrassen and a bottling dedicated to his grandfather, the “Wilhelm Friedrich.” As you can imagine, the Schlossberg is a warmer, site, angled to the sun. This is the most powerful wine Lukas makes. Finally, the Schlossberg Terrassen is produced from a site higher up in the mountains, a terraced site on top of the forest only recently cleared, exposing ungrafted vines planted in 1926 – they are nearly 100 years old. While at one time there were almost 100 hectares of these terraced vineyards going up into the forest, today there are only around two hectares remaining, roughly half of which is his. He says it is a tremendous amount of work and a very cool site (after 3pm the site gets no direct sunlight), yet the wines are singular.

I love this sentence he wrote me about the Schlossberg Terrassen: “This is already every year quite exhausting but there are great distinctive wines from the terraces. We love it.“

And as an exclamation point to the collection, Lukas farms one small plot in Neustadt with very unique Gneiss soils; this he bottles as the “Wilhelm Friedrich,” a tribute to his grandfather.

As for the viticulture and winemaking, Lukas is farming 100% organically. He is not certified. “I do not do this for marketing,” he says.

It’s hard for me to gauge, exactly, his technique for picking or ripeness. The wines have a distinctive edge, a rapier-like acidity, but Lukas does not pick very early, though he also does not want to be too ripe or over-ripe. Most of the dry wines clock in around 12-13% and are powerful, so Lukas is clearly not jumping the gun. On the other hand, nearly all the wines go through malolactic fermentation (yes, including all the Rieslings) yet still they have this incredibly pushing and incisive acidity, so something very special is going on here.

Three chapters and we’re back to the heart of the mystery that is Hammelmann.

Lukas tends to press directly; the wines ferment in used barrels of all sorts of sizes and ages. The basic estate wines and village-level wines are bottled after one year unfiltered. As they can sometimes be delicately cloudy, Lukas bottles them as “Landwein” so he doesn’t have to have them approved by the local tasting board. The result of this, however, is that he cannot use the village names, thus his village of Zeiskam has to become “Zimkaes” and Hochstadt has to become “Dhochsatt” or “Haschdott.”

The Grand Cru single-vineyard bottlings see nearly two years in barrel and because of the natural clarification of time, these wines are also bottled unfiltered yet are clear enough to consistently pass the tasting panel. Thus these are Qualitätsweins and can state their single-vineyard origin. All the wines see somewhere between 20 and 40 ppm SO2.

This is a lot to take in, I know…

But I believe these are a singular expressions of the Pfalz – and they will be wines of consequence. It’s time to take notice.