This is the “wild Mosel,” very literally.

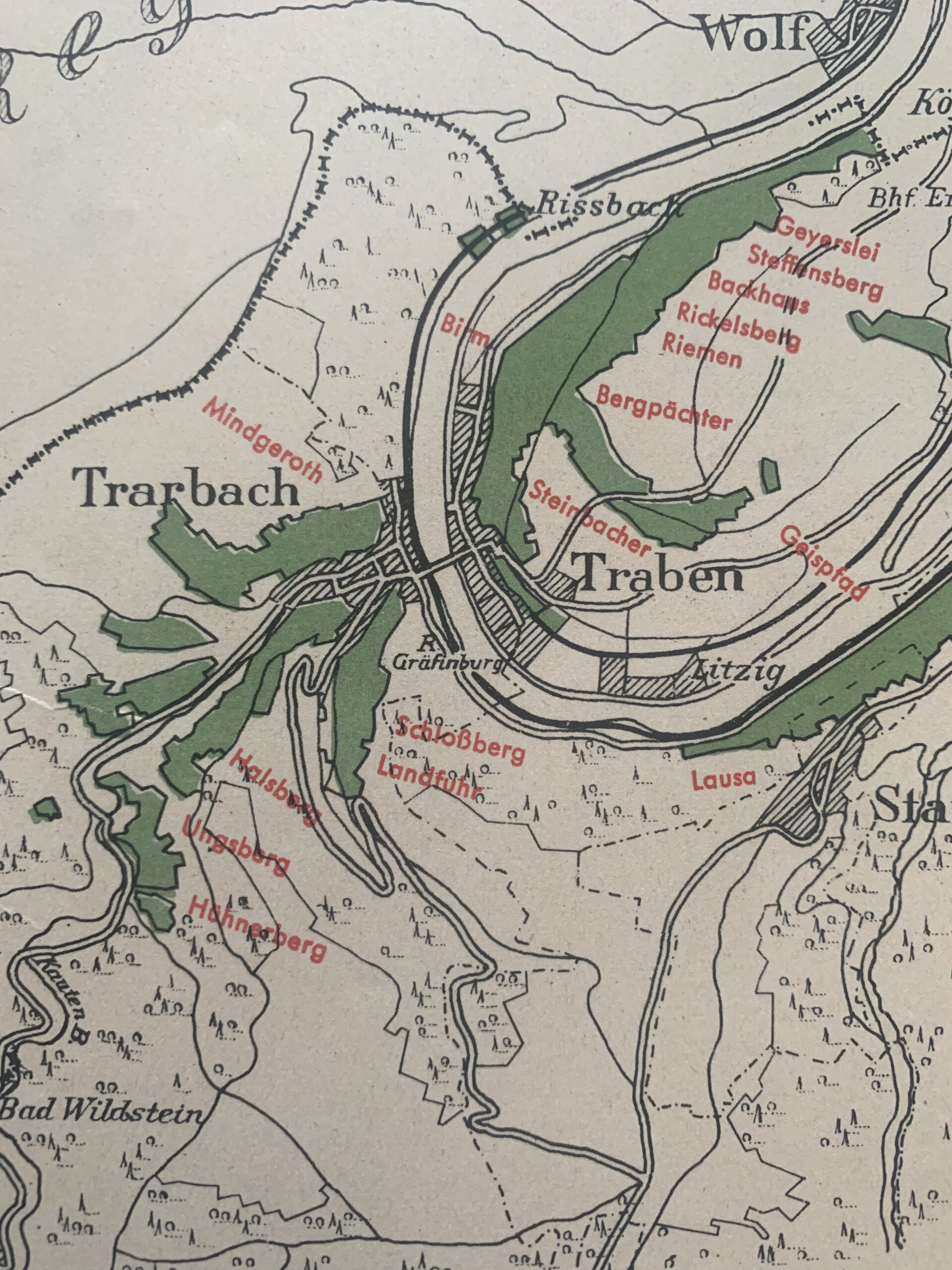

Jakob Tennstedt has found perhaps the two wildest vineyards in the Mosel, hidden deep within a side valley behind Traben-Trarbach (home of Daniel Vollenweider, with whom Tennstedt apprenticed for a short time).

Standing in these steep vineyards one looks south not over the Mosel, but over a dark, dense forest as far as the eye can see. With blue skies and sunshine this place seems as idyllic and luxurious as the garden of Eden (see the photograph below); with storm clouds on the horizon and wind rattling the leaves it can feel foreboding, even dangerous. Maybe it is the sense of isolation that makes the emotional register in these vineyards feel extreme.

Although we are only a few kilometers from the traffic and tourism of the Mosel, this place feels wild. Aside from a quiet road running up the valley and a few scattered houses and buildings, there is only forest. Jakob likes this isolation, the quiet. He tells me he didn’t want “the influence” of other people in a way that is both very deeply felt and very vague.

Being alone, on one’s own path, is a meta-theme here.

The location, however, is not the only wild element. Jakob’s entire approach to winemaking is, in the context of Mosel Riesling, largely unheard of – it is wild.

Jakob picks solely on taste and feeling; he does no measurements at harvest. Although his wines ferment to complete dryness he allows all healthy botrytis in his selections; this is quite unusual. Fermentations take place in old Fuders over many, many months – they can take more than a year. Jakob then tastes the wine, constantly filling the barrel, until he thinks it is ready to bottle, a decision made, again, by feel, by intuition.

A wine may be in barrel for well over two years before being bottled, unfined and unfiltered and with no sulfur. He neither encourages nor blocks malolactic conversion.

Verily, the resulting wines access textures and flavors that are simply unprecedented, exceedingly rare, or, to be honest, explicitly avoided in most Mosel Riesling. The sensory array is kaleidoscopic and confusing, from tobacco to prosciutto, yogurt, nutmeg, clove, bee pollen, bitter nuts, pine needle… only a humble attempt to begin what would be a dizzying, and inevitably incomplete, list.

The word “wild” suggests something of the singularity of these wines, but it doesn’t quite convey the broader sensibility of the wines, which isn’t uncontrolled or unmeditated at all – in fact it is exactly the opposite.

Jakob’s wines, like his person, are calm, still, meditative – poetic, yes, but also clear in purpose.

They have force, yet they are not forceful. Their drive is curved, rhythmic, like the movement of a shark’s tailfin, swaying – pushing – left and right with a calm, almost methodical rigor.

Jakob Tennstedt is making deeply, deeply personal wines. As such, they may not appeal to everyone.

In fact, because so many of the wines’ obvious characteristics are so different (in fact exactly opposite) from what I am normally attracted to in Mosel wine, I’ve had to really reflect on what, exactly, I find so compelling in these wines – why I keep coming back.

Part of it is just the astounding quality.

I loathe this word but the wines have “breed.” What I mean is that they have a very obvious balance, a near-perfect seamlessness, a shimmering quality. You may not want oxidation; you may not want your Mosel wine to smell like amaro – I feel you – but these are matters of personal preference.

What is not a matter of opinion is the extreme finesse and exotic-yet-controlled beauty these wines display, easily, naturally, like the greatest of great white Burgundies. The aesthetic is different, yes, but the essence is the same.

Beyond just the obvious quality, there is something deeper and more important – and more elusive. I don’t know how else to say this: There is something about the conviction of these wines, the authenticity, that I just find very moving.

As the natural wine movement ripples through Germany (admittedly a number of years after France, Spain and Italy), the Mosel especially seems to have become a sort of focal point. This is easy enough to understand: The vineyards are superb, the vines are old and the rent is cheap. (Only the amount of sheer labor and commitment is exorbitant – because of this, these growers should be given medals.)

In many ways, this new generation of wiley natural winemakers is saving the Mosel – or at least saving many cranky, difficult and obtuse old and forgotten parcels that would have otherwise gone fallow. Because of this late arrival, the vogue, the fashion, the “coolness” of natural wine still feels new and shiny in the Mosel, in a way it doesn’t in other parts of Germany, most of which have already absorbed the tenants of this movement years ago and don’t exactly expect you to look shocked when they say they’ve done excessive skin contact, or bottled a wine cloudy or with no sulfur.

Oh yes, there is a tidal wave of “hip” natural Mosel wine coming soon, pouring into markets around the world. Much of it, as with any movement, is just fashion. However, some of it will stand the test of time and begin to write a new chapter of what the Mosel is, or can be.

And while Jakob can certainly be grouped together with some of these young growers, the truth is Jakob has very little to do with this movement. Jakob is following something very personal, something internal. He speaks quietly about this movement, saying he thinks it is “a very good path, but I am going my own way.”

Read more about Jakob’s place within “The New Alt Mosel” in Vol. 1 of Trink Mag, an online plublication devoted to Germany and its neighbor’s wines.

His wines are not trying to shock you; they are not loud. There are no crazy labels, no particularly daring design or wild colors, there are no clever wordplays and no rhymes. The project isn’t underwritten by any larger institutions, trying to grab a bit of the “cool” of natural wine.

This is just Jakob, alone, farming 1.4 hectares of old vines on the edge of the Mosel.

As the wines themselves are unfined and unfiltered they would never pass the Mosel wine authorities’ taste tests. They are “Landwein der Mosel,” and as such, they cannot declare their village or vineyard, even though Jakob does hold to the custom of single-vineyard bottlings. Jakob found a beautiful solution to this problem: he simply names the wines based on a bird or insect that seems to embody the vineyard. Again, not revolutionary or shocking, just subtle, poetic.

It’s curious, as deeply individual as Jakob and his wines are, he is only farming Riesling and he is only bottling single-vineyard wines. These are both, obviously, deep traditions in this famous valley. The labels, far from being wild, are restrained, simple.

Counterintuitively, the more you truly look at Jakob’s project, his wines, the more classic it feels in many ways.

From the very beginning, Jakob has farmed both organically and biodynamically; this is critically important to him. He will have organic certification with vintage 2022. Yet, beyond this, more than nearly any other grower we work with, Jakob seems to view his vineyards as gardens, which makes him consider things in very unique ways. An example: One of his vineyards (Ungsberg, the “Musari” bottling, photographed below) has a large number of birch branches and natural logs used to train the vines instead of wooden poles or steel posts.

“Why?” I asked when we first met. “Because they are beautiful,” he said.

Jakob welcomes all sorts of flowers, wild grasses, insects, butterflies and animals into the vineyards. Only hand-built, electric-wire fences seem to interrupt the natural flow from the forest to the vineyard – wild boars and deer, almost exclusively it seems, are unwelcome in the vineyard.

As personal as this all is, it should come as no surprise that it is, not small, but human-scaled. Jakob began in 2017 making only around 700 liters. Currently, he is only farming 1.4 hectares in this side valley. Perhaps, he says, he may some day farm two hectares, but that is all. Nearly all the vines are 50 to 100 years old, roughly half are ungrafted.

To break it down exactly. At the moment Jakob is farming 0.7 hectares in the Hühnerberg. From this vineyard he makes a wine called “Waldportier,” a type of butterfly. He farms 0.5 in the Ungsberg from which he makes two wines, the “Musari,” (a type of buzzard) from an old-vine, terraced parcel higher in the vineyard and “Valke,” (a Kestrel) from a lower parcel. Jakob farms 0.2 hectares in the Schlossberg. From here he makes a wine called “Mauerfuchs,” another type of butterfly. Finally, to be comprehensive, there is a small parcel in the cool Taubenhaus vineyard which Jakob gave up after the 2020 vintage – it was simply too much work. From this site he bottles the “Perlmutt” from which the final wines of 2019 and 2020 have yet to be bottled.

Please watch our tour of Jakob Tennstedt’s singular vineyards, deep in a side-valley behind Traben-Trarbach, brought to us by the good people of Google Earth. We begin with a panoramic look at the well-known “Hollywood Mile” of the middle Mosel, from Bernkastel to Erden – just to give you context. To get to Traben-Trarbach, our second stop, we only have to glide downstream to the next major turn of the river to Enkirch’s Ellergrub and Gaipsfad, Weiser-Künstler’s Grand Crus. Just at the entrance of the side valley lies Daniel Vollenweider’s estate overlooking the Mosel river, and behind the forests enveloping his estate is Jakob’s first holding of Taubenhaus. Directly across the valley is Schlossberg before we move deep into the valley to the trio of Ungsberg and Huhnerberg, dramatically further from the river and truly on the edge of the Mosel as we know it.