I first met Shelby Perkins on a cold, rainy day in the Eola-Amity Hills.

Jess Miller and I ran through the cold mud to Shelby’s house; we nearly jumped into the warm family room, quickly shutting the door behind us to keep out the elements. It must have been the fall of 2019?

Inside, wearing sweatpants and wrapped in a blanket (she had already been in the vineyard most of the morning), Shelby warmly greeted us by asking us to grab more cheese out of the fridge.

We grabbed the cheese, what else could we do?

There were mountains of glorious and varied cheeses. We handed them to Shelby who threw them all nonchalantly into warm pot to melt down.

“God,” she exclaimed loudly to no one specifically: “You know when you just have to have some #@*!!!ing cheese???” And with that she ripped up a loaf of bread and dipped it in the melting cheese.

I had known her all of five minutes and I thought to myself: This person is wonderful.

The next few hours are something of a blur; few times in my life have I met someone as clearly and as distinctly brilliant as Shelby. I had the sense that she had around ten to twenty distinct thoughts at all moments of every second, simultaneously, and the effort and art of her existence was trying to filter all these thoughts into a few basic sentences, so you know, bumbling average humans like me might be able to keep up.

The next few hours are something of a blur; few times in my life have I met someone as clearly and as distinctly brilliant as Shelby. I had the sense that she had around ten to twenty distinct thoughts at all moments of every second, simultaneously, and the effort and art of her existence was trying to filter all these thoughts into a few basic sentences, so you know, bumbling average humans like me might be able to keep up.

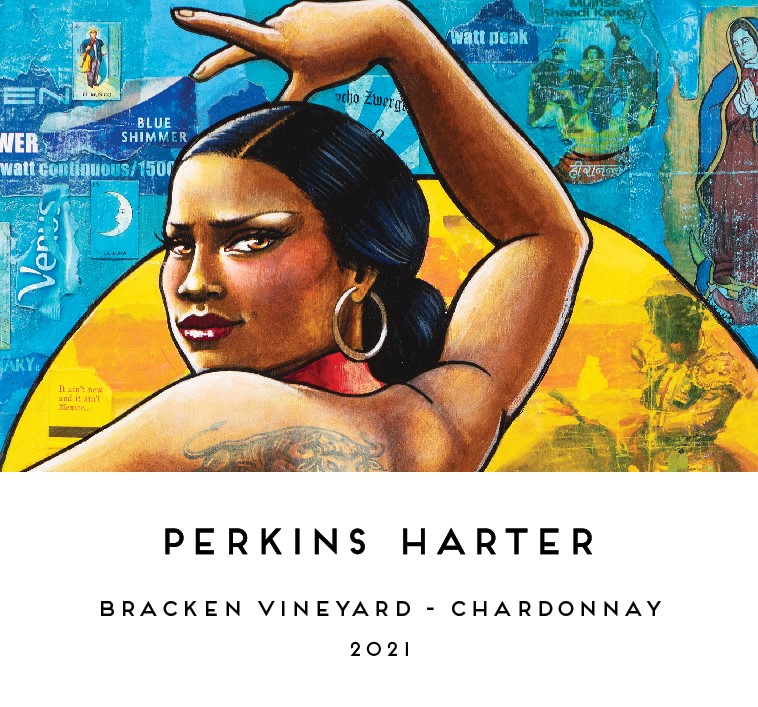

We discussed, in no particular order: cheese, her collection of paintings hung gallery-style all over one large wall (Shelby went to Skidmore planning to study studio art and remains a lover of the visual arts, as I am myself, being basically a failed art historian – her labels always feature the art of friends), vineyard spacing when planting, Burgundy, cheese, the best boots for mud, the push and pull of oxidation versus reduction, Oregon and the wine scene, cheese, biodynamics, environmental policy, nuclear waste, cheese and voles.

I was feeling manic, excited, confused and craving cheese when we finally sat down and Shelby opened a few Chardonnays for us.

She said something like: “I don’t know, these are the first Chardonnays I’ve ever made so we’ll see how it goes.” And what came next were very good and distinctive and specific and focused Chardonnays.

I sat there silent and Jess and I looked at each other and Jess gave me those eyes that said something like: “I told you jackass; she’s fucking awesome.”

Shelby and her husband Peter (the Harter of Perkins-Harter) had just bought the Bracken vineyard and moved their lives to Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Both of them have the whirling-dervish-resumés common among freestyling, environmentalist, hippie-intellectuals with acute and sharp intellects. Shelby had minors in geology and environmental law before studying environmental law at the Vermont Law School where she got two law degrees (why stop at only one?) and then a certificate in European Union law from the University of Amsterdam. From there nearly a decade was spent, on and off, as an attorney-advisor for the U.S. Department of Energy working on issues around nuclear waste.

It’s all enough to lead to some serious burnout and the desire to, well, just tend one’s garden, which is sorta what she is now doing with her fifteen-acre garden mostly planted with Chardonnay and Pinot Noir vines. This garden is called the Bracken vineyard.

Since 2018 she has been tending this site and learning its ways. I can repeat as easy as anyone else the statistics: around 700-foot elevations, volcanic soils, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay at various spacing metrics (5 x 7 and 4 x 7). Shelby is farming the site organically and in 2019 started bringing some biodynamic practices into the vineyard.

What’s harder to articulate is the style, the voice of this vineyard. This is what is slowly emerging, vintage after vintage. This is the story we’re reading; the story that is in fact being written, in real-time, by this brilliant person and the other growers who buy fruit from this place – which include an a-list of who’s who in Oregon winemaking, from Walter Scott to Love and Squalor, Beck Family vineyards and more.

Shelby, for her own wines, has learned that the site seems to have a special kick to it, the cool-climate verve of Oregon’s Willamette being emphasized in the Eola-Amity Hills, especially in the Bracken vineyard. As such, Shelby wants to both preserve and in a way challenge the acidity. While she used to work quite reductively, as is the vogue especially in Oregon these days, she now leans more into a gentle oxidation during pressing – ultimately she believes this is better for the long-term stability of the wines. The wines naturally have a very high acidity and a very low pH, so they are quite stable. While she will top off regularly during fermentation, during the élevage she will let things float a bit longer (4-6 weeks). All fermentations are natural and she avoids filtration at all costs.

The results are lifted, uncommonly precise and alive. They feel cooler and more ethereal than nearly any other wines I’ve had from Oregon. But this is just the beginning…

I can’t wait for more – hopefully with a big pot of melted cheese somewhere on hand.