This is the first Mosel estate we’ve taken on in almost a decade; let that tell you something about how important we think it is.

Even though we are blessed with our growers in the Mosel, well, we’ve always wanted more. Why? This is a magical place; its wines are unlike anything else on earth. We wanted more of this place.

Even though we are blessed with our growers in the Mosel, well, we’ve always wanted more. Why? This is a magical place; its wines are unlike anything else on earth. We wanted more of this place.

So, for nearly a decade, we’ve been driving up and down the 100-some-mile length of the river, backwards and forwards, getting insider tips from growers, looking at old books and journals, tasting with anyone and everyone we could… and nothing.

Or at least, nothing exactly right, for us.

And then, in the summer of 2021, John and I were driving through the Mosel and we got an Instagram DM from a young grower who had seen we were in the area. Just so you know this isn’t some narrative bullshit, I went back and found Julian’s first IG DM as well as my response: it’s posted below and to the right.

“Did we want to come by and taste some Rieslings?” he asked.

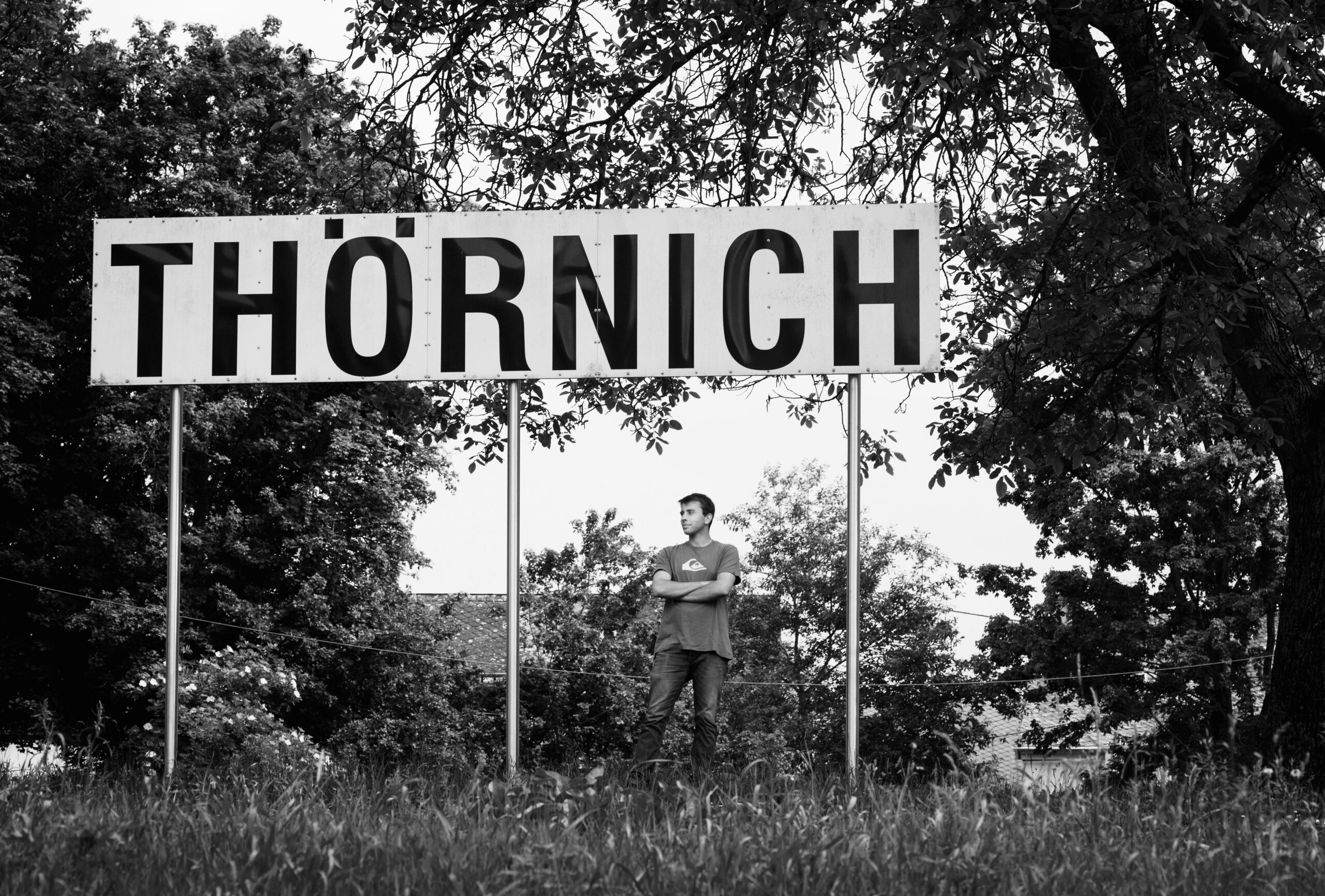

Now, the young grower was Julian Ludes (pronounced “LOOD-es”) whose grandfather Hermann Ludes had started the eponymous estate in the 1950s. We had of course heard of the place – an old school, legendary-in-a-quiet-sorta-way estate. Weingut Hermann Ludes has flown under the radar for decades for a number of reasons. First, the village Thörnich is located in an upper-section of the Mosel, far away from the famous “Hollywood Mile” of the Mosel. Further, Thörnich is legendary for shaping wines that are raw and tensile; the wines of Hermann Ludes especially can be brutally structured. In other words these are not easy wines. Second, the founder’s son and Julian’s uncle, also named Hermann Ludes, speaks no English and has made, over the decades, exactly zero attempts to market himself or to try and placate any whims or fashions, customers, exporters, importers or journalists. He has made his wines his way; he has spent a lifetime in his vineyards. That has been enough. (Pictured below, from left to right: Julian Ludes and his uncle Hermann Ludes.)

Yet, the best, best wines of this village and its famous Grand Cru site Ritsch can sit on the table next to any Mosel Riesling. For sure no German wine importer worth their salt hasn’t secretly (or overtly) dreamed of working with an estate that farms the awesome, angular, ferocious and intimidating Ritsch.

Many have said Thörnicher wines have more in common with Saar or Ruwer wines; there is something just tough about this place and this site.

The older wines from Hermann Ludes were and are serious insider wines; the cellar still has some treasures 20+ years old. Personally, I had always bought what I could. The wines are thrilling.

And yet, for us somehow the estate – and by this I mean the current estate and the current wines – had just sort of disappeared behind the reputation of the older wines. It doesn’t really make any sense; I admit as much. It’s like ignoring Jasper John’s complex and truly amazing works of the 1960s, 70s and 80s because you saw one of his flag paintings from the 1950s and were like, “Yup, he’s a genius. NEXT!”

But that’s where we were.

So John and I accepted the invitation, as we had for hundreds of other tastings, because we were curious. I don’t think we had any expectations.

Was it by the third or the fifth bottle that we knew – WE KNEW – we wanted to work with Julian? I can’t exactly say. I can say this: I knew it very deeply and very quickly. And I could tell John knew it very quickly and very deeply.

These are truly old-school Mosel Rieslings; in my mind these are the rustic, transparent, bracing – even a touch brutal – Mosel wines that were probably common decades ago. Yet this style has been nearly forgotten, pushed aside by the riper, fruitier, easier style of plush-and-giving Mosel wine.

To my mind, Hermann Ludes, Ulli Stein and Erich Weber are the current canonical masters of this style. The best Ludes wines also have something of the sleek tension, the force that is the calling card of Julian Haart’s wines. Yet perhaps the closest comparison in our book is with the wines of Weiser-Künstler, with their faceted, crystalline and largely mineral-and-earth driven language. Obviously, all the Mosel growers in our portfolio have some relationship to this style – there is a reason we are attracted to all these wines.

Either way, Julian Ludes has been working with his uncle since 2017 and they are continuing this genre of unflinching, unapologetically structured, old school Mosel wines. Or, from another perspective, they are simply one of the few estates carrying the torch forward.

Julian and his uncle both seem to know exactly what they want to do and why. Here’s an example: In vintages 2016 and 2018 they didn’t like the grapes or the wines and so they decided together to just sell everything off bulk.

Everything. That’s a year’s worth of work, sold at a discount.

As the kids say: “No fucks given.”

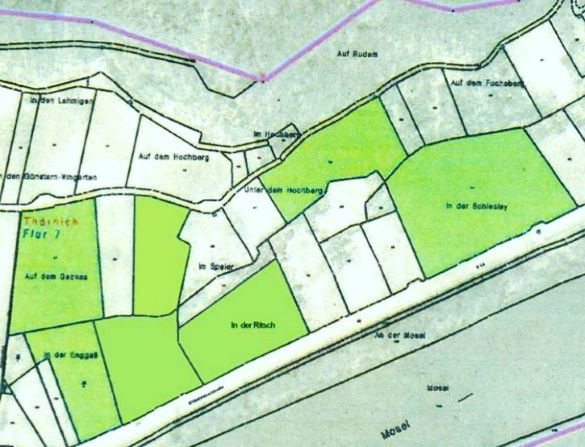

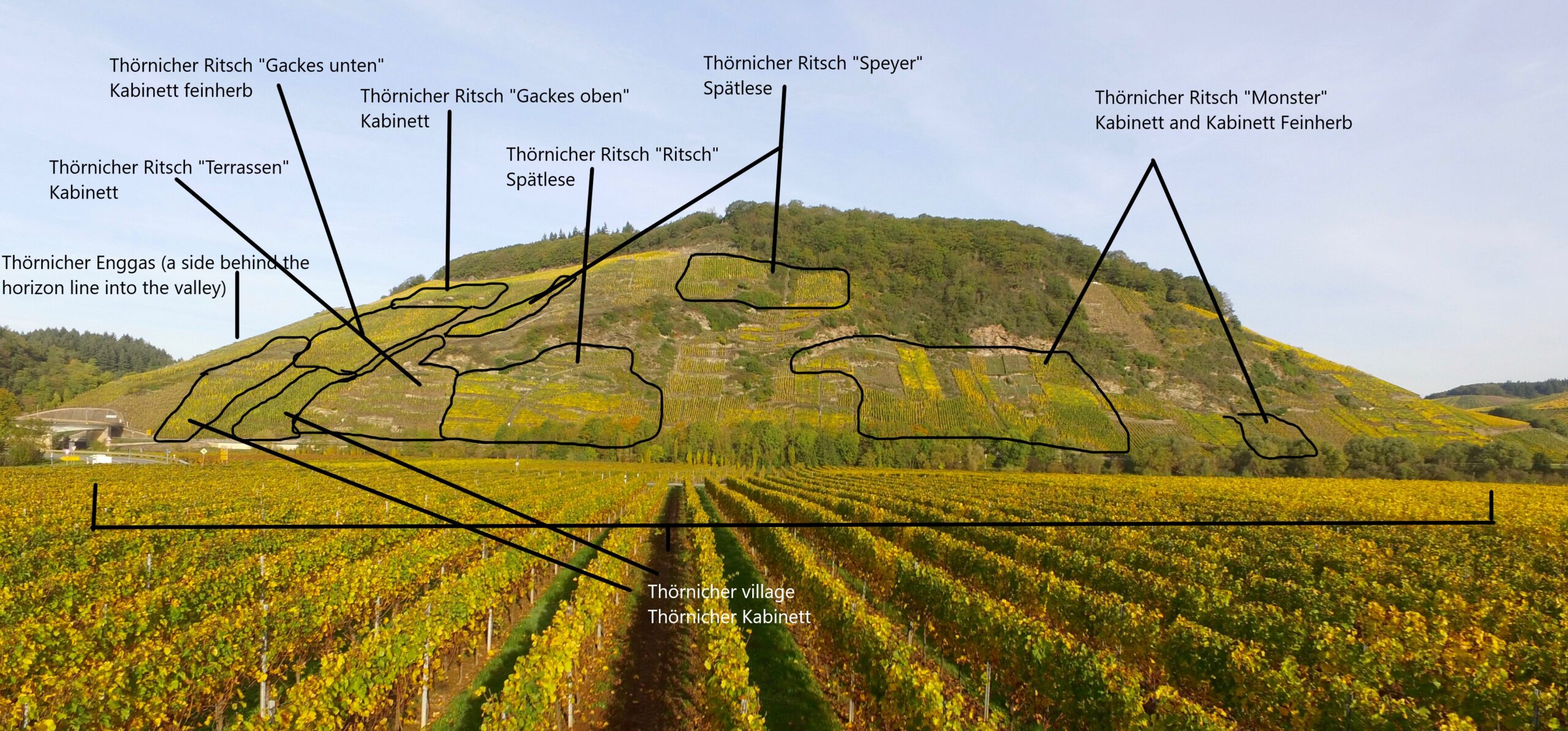

Currently, the Hermann Ludes estate is the largest single owner of Thörnich’s Grand Cru Ritsch vineyard, owning most of the old-vine, ungrafted parcels. While the Ritsch does have a prime south, south-west exposure, two side valleys open up on either side of the site, exposing it to the frigid air from the plateau of the Eifel – you can see this quite clearly in the photograph above. This cold air rushes into the vineyard at night; it is demonstrable. During harvest here the acid levels simply do not drop in the same way they do in most of the other sites of the Mosel. Take a look at the photo above; you can see in the arc of the horizon line how “open” the site feels compared to most Mosel vineyards. For those of you familiar with the wide-valleyed feel of the Saar, there is something vaguely similar-feeling here.

Julian’s uncle was forced to quit school and start working the vines in the 1970s when his grandfather had injured his back and couldn’t manage the work. Uncle Hermann began to lower yields dramatically, pruning all the vineyards to only one cane. The villagers took note and told the grandfather his son was crazy.

The uncle came of age as Mosel wines became ever-sweeter, ever-more plush and fruity. Yet he stood firm against basically every financially-beneficial trend of the 1980s and 1990s, remaining true to the historic wines of Thörnich, of the Ritsch. Hermann Ludes made wines that required time just as the wine world entered the era of immediate gratification. Julian’s uncle never flinched.

Julian, by all accounts, has a similar fortitude. His uncle is clearly a role model, yet they share a deeper respect for what Thörnich is, for what the Ritsch can be.

In total, they are farming around 11 hectares. Six hectares are flat vineyards in and around Thörnich. Before they were only producing wines, this is where the animals would graze. Today, most of this fruit is sold bulk, though they may use some of the gravelly flat sites to blend into the basic “Hermann,” or not, depending on the quality of the vintage. I asked him about these sites; if they believe in steep-slope viticulture (and clearly they do, see next paragraph) why not sell the flatland vineyards? Julian responded quickly: “This is our family land; we will never sell a vineyard.” These vineyards also provide an easier income with the bulk sales; in a way they help subsidize the rigor and the expenses of their steep-slope viticulture.

From the village-level Thörnich bottling on up, all the fruit is from steep slopes. Julian and his uncle own a bit more than four hectares in the Ritsch; they also have tiny holdings – a bit more than a hectare total – in the Thörnicher Enggas, Klüsserath Bruderschaft and Pölicher Held. The Ritsch, however, is the diamond in the crown – and a big diamond at that. The average vine age here is about 75 years old, many of the vines are ungrafted. Every site they own in the Ritsch is inaccessible by any machine; terraced vineyards with walls at the top and the bottom. Absolutely everything must be done by hand.

While Julian says they are nearly always the first estate to harvest in the village, he also says they are normally the last out there harvesting. Either way, yes, they are looking for healthy grapes that are ripe yet still have some green. The estate direct-presses nearly everything; while they have a pneumatic press, they do not rotate it, so it functions a bit more like a basket press. The press cycles are very low-pressure and very long. Each parcel is fermented separately and naturally. Since the early 1990s the estate has used only stainless steel; since 2000 they have used only screw caps.

As for the screw caps, the estate had problems in the 1980s with cork and the uncle came across screw caps in the later 1990s. By the vintage 2000, he had made the decision to switch. At the time – over 20 years ago – no one used screw caps in the Mosel. They all called him crazy, the same way they did when he began training all the vines all those years ago.

Now, of course, screw caps are common. I’ve tasted the 2000 Kabinett Trocken (bottled under screw cap); more than two decades of age and it is superb. I’m not the biggest fan of screw caps, but I can’t deny the wine’s beauty.

As with many of our producers, the true passion here is the Kabinett – whether it is dry or off-dry or fully fruity. “The Kabinett is the greatest style on earth,” says Julian to me offhandedly, as if acknowledging something as irrefutable as the time of day or the color of my shirt. The estate rarely does Auslesen; they avoid BAs, TBAs or Eiswein. “These are wines for points, not drinking,” says Julian.

What they seek, no matter the exact ripeness or level of residual sugar, is a wine that crackles with tension, that has rigor and structure. If the wines are too bracing, too brisk to be exactly legible – or even perhaps friendly! – in youth, they simply require two things that seem to be rarer and rarer every year, despite all our brilliant technologies and automated efficiencies: time and patience.

For that reason alone, these wines are so important. But for the acid-head, for the most extreme lover of the Mosel and its salty, slatey, cold-as-a-mountain-stream mineral core, these wines will be a delicious, singular, revelation.

Perhaps they will be the Mosel you were looking for.