“Lauer has gone cult.”

I keep the quote above largely for sentimental purposes. It was first penned by me, in the summer of 2011, as I was trying to come to terms with the stratospheric rise of Lauer, who was then still a bit of a newbie on the U.S. scene. It’s funny to read now, over a decade later, as Lauer has been, unquestionably, established as one of the greatest addresses in Germany.

For purists, there is nothing like the Saar. It is arguably one of the greatest, most unique wine-growing regions on earth. The core of greatness in the Saar is intensity without weight, grandiosity without size. Frank Schoonmaker put it best in his 1956 tome The Wines of Germany: “In these great and exceedingly rare wines of the Saar, there is a combination of qualities which I can perhaps best describe as indescribable – austerity coupled with delicacy and extreme finesse, an incomparable bouquet, a clean, very attractive hardness tempered by a wealth of fruit and flavor which is overwhelming.”

Yes, this is the Saar and Florian Lauer is currently one of the greatest winemakers in this sacred place.

Florian’s general style is exactly the opposite of his famous Saar neighbor Egon Müller. At Lauer, the focus is on dry-tasting Rieslings as opposed to the residual sugar wines of the latter. For this style, there are really only two addresses in the Saar (though more come online every year, trying to chase the style): Lauer and Hofgut Falkenstein.

Employing natural-yeast fermentations, Lauer’s wines find their own balance. They tend to be more textural, deeper and more broad-shouldered. Yet they have a preternatural sense of balance, an energy that is singular. Yet the hallmarks of the Saar are there: purity, precision, rigor, mineral.

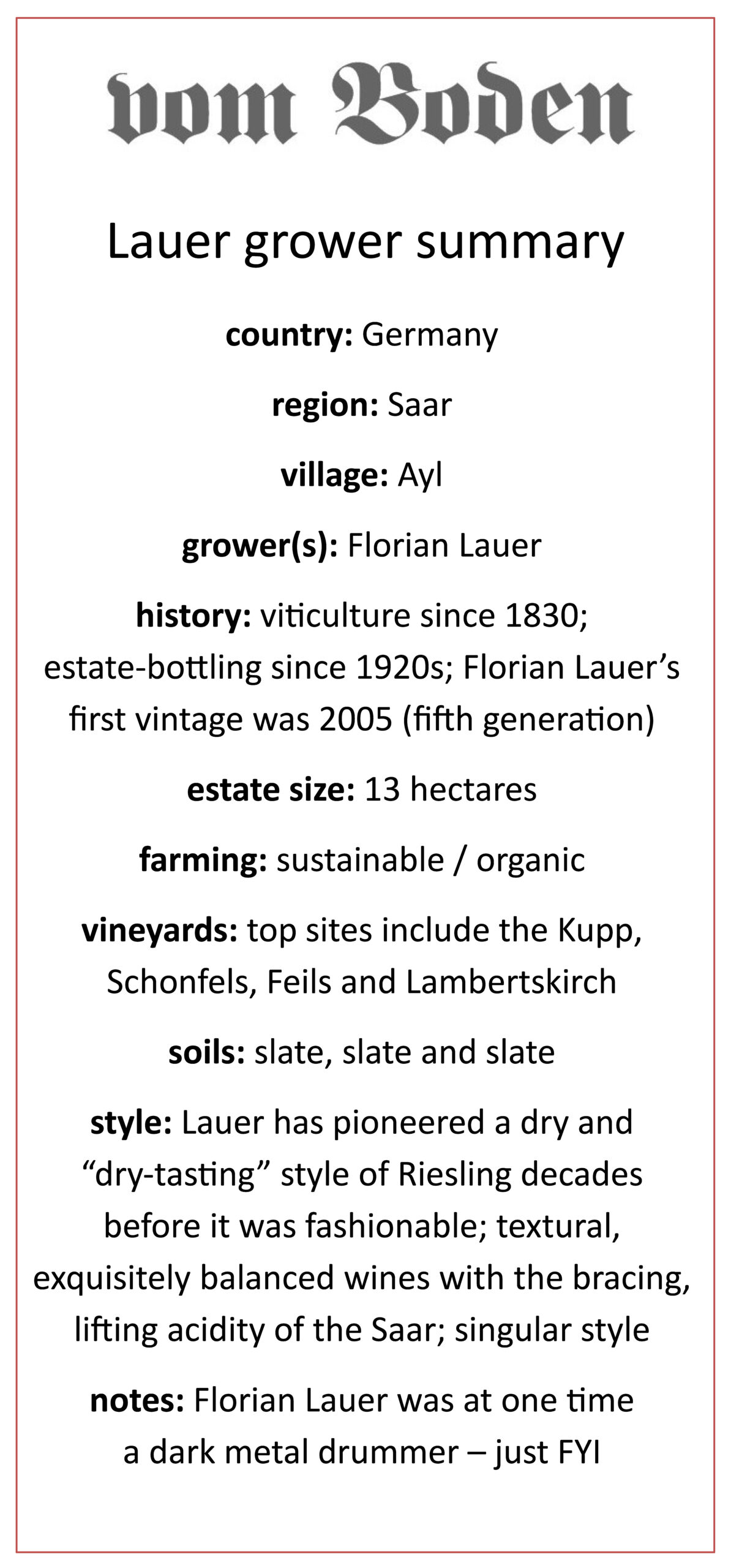

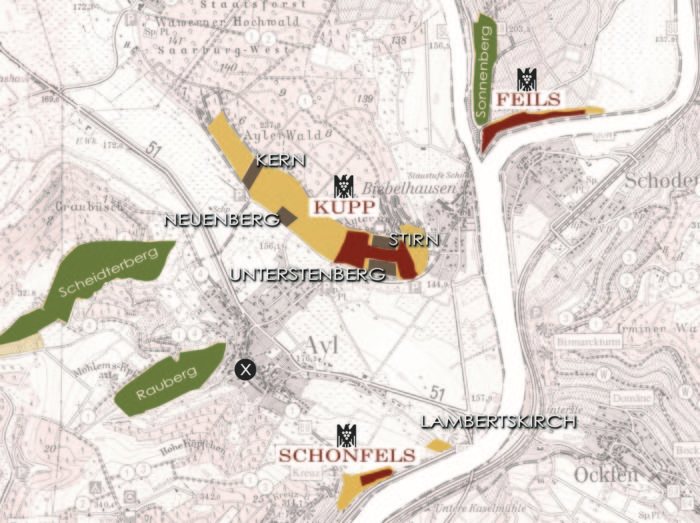

Florian’s playground is the breathtaking hillside of the Kupp, pictured to the right. Though the many vineyards of this mountain were unified (obliterated?) under the single name “Kupp” with the 1971 German wine law, it has been Florian’s life’s work to keep the old vineyard names alive, to keep these voices alive. He has been fighting this fight since his first vintage in 2005 and only with an update to the law in 2014 can he now legally use the older vineyard names such as Unterstenberg, Stir, Kern and Neuenberg.

Florian fought the law, and he won.

In addition to the expanses of the Kupp, Lauer farms three other important sites, Feils (historically called Saarfeilser, don’t ask me why they changed it) directly across the river and the precipitous, cliff-vineyard Schonfels, a bit upstream from the other two sites and, finally, the once-famous Lambertskirch, just a stone’s throw from Schonfels. This was a site with a huge reputation in the 19th and mid-20th century, yet it was abandoned. Lauer cleared the site and replanted it himself.

For an even more in depth overview of the Lauer vineyards, check the video below with an in depth description touring these sites via Google Earth.

At the very bottom of the page, the tabs discuss all about Florian’s various bottlings. If you’re nutty enough to read all this stuff, you’ll graduate with your PhD in Lauer. It’d be great if you’d then go and explain it all to your friends.

We begin with an overview shot of the Mosel—the pin is dropped in Piesport where Julian Haart’s main sites are. Up in the top right of the screen you can see Traben Trarbach where Weiser-Künstler and Vollenweider are and a few bends of the river beyond that is Alf where Ulli Stein and Phil Lardot are. We then take a brief stop in the village of Ayl where the winery is located in the heart of the Saar.

Now moving to two eastern facing slopes we have the Rauberg and the Scheidterberg which circle around the backside of the village. The village wine No. 25 comes from Rauberg and the coolness brings the intense saltiness and bright acidity. Scheidterberg is considered a kind of 1er cru, nearly grand cru especially in the center where the warm section is facing south.

Next with slide five is the south-east kind of tail of the Ayler Kupp–called “Wald” on old maps–where there are 70 year old plus ungrafted vines. This is where the wine called “Senior” comes from, named in honor of Florian’s grandfather who loved this wine and would frequently reserve the cask from this site for personal consumption.

Then, the Kern, one of the most complete of the Ayler Kupp wines as it has a whole cross section from top to bottom, named after the industrialist who cleared this site in the 19th century. The vines are old here, well over 70-years-old, so the wine has some stuffing. It is well in that off-dry style, yet, with Lauer, it’s always about the balance.

Next is the curious Neuenberg, one of the most historically important parcels in the Ayler Kupp. This site has wet fields directly below which create a cool and damp haze around the vines, leading to very clean and good botrytis, giving a concentration and slight exotic quality to the wines from this small site. Florian’s father planted these vines with future generations in mind, as the site was still too cold to make great wine in his day.

We arrive at the warmest and oldest part of the Ayler Kupp with slide eight. First with Unterstenberg. Even in Roman times they noticed the snow melted quickly in this area and planted grapes in the earliest farming of the Saar. This is the foot of the hill and benefits from hundreds of years of weathering of the slate at the top of the slope, the topsoil here is full of slate rocks.

Next is the “Filet” section of the Kupp where the GG comes from, this was replanted in 1956 by Peter Lauer Senior and this is the steepest and warmest part of the slope. It is perhaps the most elegant of the GG wines, with fine layers and a suave, polished finesse—it has both fruit and depth and mineral core of slate and salt.

Finally at the top is Stirn, translating to Forehead or the summit of the slope. Here there is very little water and the interplay of that and the coolness of the stone makes a kind of baby Kabinett, usually quite off dry and soaringly angelic.

The Kupp’s east side is where wines such as No. 3 come from, a kind of spiritual kin to the Stirn wine. Again, this is another area that has benefited tremendously from the warming climate, now turning out wines of incredible finesse and balance.

Further south in the village is one of the greatest sites of the Saar called Schonfels with 107 year old vines. While the vineyard has always had a huge reputation, Florian’s father let the site go fallow in the 1980s. The reason? It’s too damn expensive and too difficult and dangerous to farm—because the site is so steep and “ends” in a rock face that drops a few hundred feet to a street below, harvesters must be harnessed in, via a carabiner, to a tractor parked at the top of the vineyard. There can be no slipping here; it is truly a matter of life and death. Florian’s decision, in the late 2000s, to rehabilitate this site was equal parts daring, brilliant, insane, and potentially financially crippling to the estate.

Lambertskirch is the next small site on slide thirteen, cleared of the overgrown brush in 2010 by Florian, this was another reclaimed site like Schonfels but unfortunately the vines needed to be replaced—replanted from selection massale cuttings of the oldest Riesling vines at the estate.

We move to the north with the Sonnenberg which is a site that has come online in the last few decades thanks to the Saar channel that now warms this site—previously it was hit hard with frost—this is where a number of off dry Village level Rieslings come from.

Finally is the only site that is not on slate, but on gravel—Feils is a unique site for the Saar in a number of ways. First, you’ll note that it is right up against the Saar river. The Feils is unique in its rather direct relationship with the river. Second, because the river pushes up against and flows around the vineyard, the site has a good amount of alluvial soil, especially toward the bottom. Feils is a warm site; it is also sneakily steep. Convex like a spoon, the vineyard begins mildly as you walk through it heading down to the river. However, as one reaches center-slope the incline becomes quite severe. The lowest third of the vineyard is extremely steep. The wine this site produces is one of the most textural and luscious of the GGs; from the beginning it can show a rather broad range of fruit and spice. It also tends to drink earlier than Lauer’s other GGs, though obviously this can change vintage to vintage.