The short story is that the young American Collin Wagner met a young Philip Lardot in France during harvest 2013 and proceeded to talk Philip into going to the Mosel.

The longer story is, of course, a bit more complicated, eventually becoming a love story involving another American (Rosalie Curtin) who would move to the Mosel in 2022 to work with Lardot, who would eventually marry him, start her own line of wines and then, most likely, move them all under one label.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Collin Wagner, who is now something of German-wine-sales royalty, a colleague here at vom Boden and a dear friend, was at the time a chef, intellectual, traveler, laborer. The fact that Lardot is a Finnish-born, Amsterdam-raised, introspective, pentalingual, autodidact and Curtin a NYC architect-in-training who gave up the Ivy league to work with wine in the Sierra Foothills doesn’t make the story any simpler.

But so it goes; we have some time.

The beginning for Philip is clear enough. Philip came to the Mosel and did his first harvest with Collin at Clemens Busch in 2013. Something important happened during this harvest – what exactly that was is harder to articulate. Regardless, Philip quickly decided to quit his job back in Amsterdam and return to work in the Mosel with Clemens through 2014.

The beginning for Philip is clear enough. Philip came to the Mosel and did his first harvest with Collin at Clemens Busch in 2013. Something important happened during this harvest – what exactly that was is harder to articulate. Regardless, Philip quickly decided to quit his job back in Amsterdam and return to work in the Mosel with Clemens through 2014.

The wine bug had sunk its teeth in; there was no going back to a normal life.

2015 and 2016 involved apprenticeships at places like Henri Milan, Bernard Baudry and Bertrand Jousset, though Chenin didn’t do it for him like the Riesling did (with apologies and love to Pascaline). So back to Germany Philip went in the spring of 2016. He went there with few plans: only to learn, to taste as much as he could and, hopefully, someday, to make some wines.

He ended up really digging these “Stein wines” and buying a lot of them at the cellar door. That’s where the relationship between Lardot and Stein began. By the spring of 2017 he was working with Ulli Stein. For nearly five years the two of them worked together, yet Philip wanted to make his own wines. After the 2022 harvest, the two decided to part ways and Lardot made the jump.

Now, at the exact moment Lardot left Stein, well, he needed help. The Mosel is, after all, more than anything else, a place of labor. Many of the steepest sites simply cannot be farmed mechanically; there is a lot of work that must be done by hand. And so it was that in the summer of 2022 Rosalie Curtin came to the Mosel, with a few others, to spend maybe a few months helping Lardot in the vineyards.

Curtin had come to the Mosel via stints in Oregon (with Jess Miller and Maloof among others) and with Frenchtown Farms in the Sierra Foothills. While the foothills were beautiful, Curtin felt like it was crazy, at her age and without anything really tying herself down, to not travel to Europe to work there, to learn there. Riesling had always been somewhere in her brain, and in fact she came to a “Rieslingstudy” that Robert Dentice organized in Chicago in the winter of 2021… only a few weeks after that, Lardot posted that he was looking for help and that was that. The decision was made.

For Curtin, and for many, Lardot’s wines were and are something of a revelation. There is no denying that Philip’s wines are wines of exploration, wines that push and pull expectations of what the Mosel is, or can be. Yet it’s also important to realize that as “new” as these wines feel, there are precedents. Stein, Thorsten Melsheimer and Rita and Rudolf Trossen had been experimenting with a number of the techniques that Lardot employs for decades before Philip began. It’s also important to note that these techniques are not even slightly radical, they are in fact wildly traditional in essentially every wine region except the Mosel. These techniques include long(er) élevages on the full lees, bottling unfined and unfiltered (or lightly filtered) and with lower levels of S02.

One has to keep in mind, however, that the signature Mosel acidity and form, that ultra-linear, lime-green acid-shockwave comes from blocking malolactic. And so while Lardot’s technique is laughably commonplace, it is perhaps somewhat radical in the context of the Mosel wines we’ve come to know in the post-war period. Yet Lardot’s argument against blocking malo has a good amount of logic: the Mosel is a cool climate, producing high acidities to begin with. Then you have a grape like Riesling which has one of the highest levels of natural acidity of any grape. Why do you want to block malolatic to accentuate the acidity more? (The answer, of course, is to accentuate the acidity even more.) But blocking malolactic can require a bit more S02, some filtering and the like, so Philip just leaves the wines alone, on their full lees, for quite some time, until bottling. The wines are bottled unfiltered; most see just a little bit of S02 at bottling only.

The general Lardot aesthetic presents wines of a gauzy, airy textures, though they can be quite saturating as well. As Lardot has developed, the wines have more structure, a growing depth, deep, deep clarity, a gushing minerality. These are Rieslings that are not milky or heavy by any means, but that are more coating and layered. The skin-fermented Pinot Gris is a humble revelation, tart red fruit and sous bois with a crispy acidity. The Pinot Noir is brisk and alpine. All the wines have a meditative, glowing, whispering sorta feel to them, presenting the Mosel not as a lighting bolt, but as a misty, soulful, contemplative place, deep with mineral and mystery.

Which it is.

The “Kontakt” wines are his entry-level wines. There is a white “Kontakt” made from a blend of Müller-Thurgau and Riesling and a red or rosé “Kontakt” made from Pinot Noir. While there are certain parcels (for example in Bullay) that always go into these wines, the “Kontakt” wines can also receive random single-vineyard barrels, booster shots of top-level juice that Lardot declassifies.

So yes, then there are the single-vineyard wines. This is really the heart of the project; a contemporary love letter to the Mosel… and in the end, though this wreaks of a Hallmark card gone off the rails, a love affair among Philip and Rosa and the Mosel.

Part of this is romance and love, but part of this is just the gritty reality of living in the world. Loving someone in an isolated place with a very limited set of daily possibilities, in such an extreme place, is probably not sustainable, or healthy. In the end, for Rosa to make the jump to Germany, to the Mosel… it had to be for both things: for Philip and for the Mosel. And after a few months, it was obvious for Rosa. She stayed. For both.

She has quickly become an integral part of the story.

Now, as avant-garde or non-traditional as Lardot and Curtin’s wines may appear to be, in another way they are profoundly classical. These top wines are, for the most part, single-vineyard Rieslings that have as their main concern, the place from which they come. Because they are bottled unfiltered and can be a touch cloudy, they would be subject to the rejection of the very conservative tasting panels of the Mosel. Thus they are bottled as “Landwein der Mosel” and are not allowed to carry their place-name. They get around this by the cast of characters they have invented for the labels.

“Der Graf,” the count, comes from Piesporter Grafenberg. “Der Mönch,” the monk, comes from St. Aldegunder Klosterkammer – Klosterkammer meaning the monastery room. “Der Bauer,” the farmer, comes from the St. Aldegunder Himmelreich. From this steep vineyard you can look down to a vegetable patch that the villagers of St. Aldegund take care of, thus “the farmer.” Finally, “Die Winzerin,” the first female in this lineup, comes from the mighty Palmberg; the character is based on a drawing of Ulli Stein’s mother Erna.

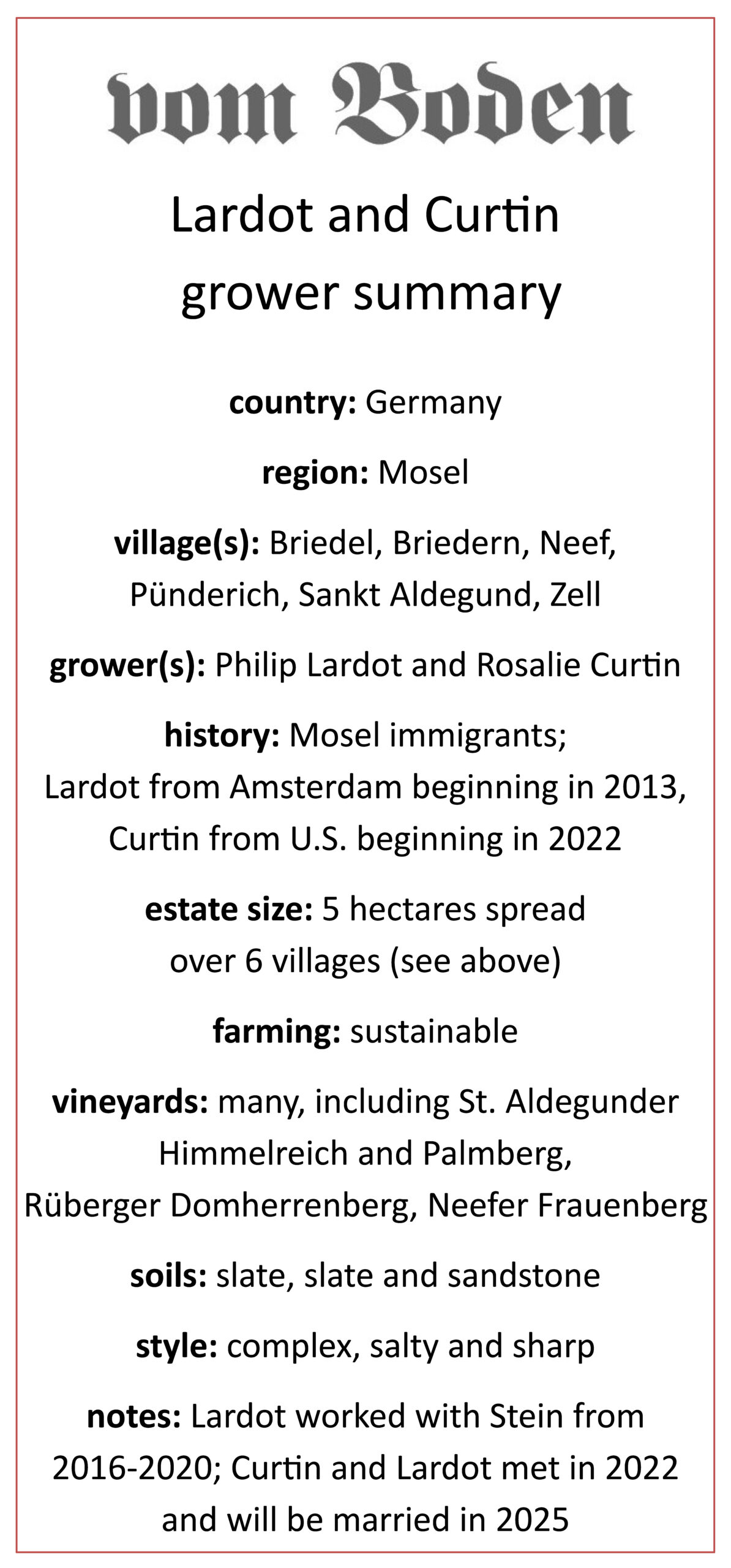

I have no doubt that when the story is written about the Mosel in the early 21st century, their wines will be a foundational part of this story. In the last few years they have expanded to nearly five hectares in six different villages, each one more obscure than the other: Briedel, Briedern, Neef, Pünderich, Sainkt Aldegund, Zell. This obscurity makes their work all the more critical; without them many of these vineyards would and will go fallow. Yet it also makes their work all the harder: There is no easy sales hook, no fame or commercial resonance to help the wines in the brutal marketplace.

And so all we can do is fucking yell: SAVE THE MOSEL. We’re only going to get so many chances to heed the call. The fucking thrill of it all, is that we get to participate in a profound act of cultural preservation and we get to taste the story being written, right now.