The old vines of Saale-Unstrut tell a tale older than “East Germany,” older than the communism and degradations of the former GDR. They tell a tale of the soil.

And Konni & Evi are among the few people here searching for these few remaining old timers, and listening to their story.

Because you likely have absolutely no context for anything being discussed here – neither the region nor the grower nor, perhaps, the main variety (Silvaner) – let me throw out some like-minded reference points, growers and wines and regions that offer something similar to the gem-like, faceted, diminutive, yet richly detailed, enthralling wine-sculptures of Konni & Evi.

First: Jonas Dostert in the Obermosel.

OK, admittedly this reference helps about one in ten thousand readers, but it’s uncanny; the two seem to have come to a very similar place on their own, unique paths.

Maybe these references will be more useful: The Sylvaners of Stefan Vetter in Franconia. How about still Champagne? Or think about de Moor and very lean Chablis from cool vintages of the 1980s; perhaps some of the quieter, more mineral-driven wines of the Jura… reaching a bit further, Muscadet – I don’t know, ****ing Txakolina???

If you are interested in any of the stuff / regions / wines or places mentioned above, keep reading. Try and find these wines. They will be worth the search.

You have likely heard very little, or nothing, of the northerly winemaking region Saale-Unstrut.

My gut is that for the first half of the century, Saale-Unstrut (and its neighbor just two hours east, Sachsen) just wasn’t making all that much interesting wine. Nine out of ten German wine books that do actually cover this region (assuming there are ten German wine books that cover Saale-Unstrut) will tell you that the region is at 51.5 degrees latitude. That’s always the first line.

Other places at the northern 51st parallel: London, for starters.

A bunch of cities in the Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan are also at roughly 51 degrees. On our own fair North American continent: Calgary, in Canada, is at the 51st parallel and might be evocative for older folks because of the whole 1988 winter Olympics reference.

Montreal, a very cool-climate region we are very interested in is at the 45th parallel, a virtual southern paradise in comparison.

The point: It’s way cold up here people.

For the second half of the twentieth century, after WWII, well, both these growing regions (Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen) became part of East Germany and the eastern block of communist countries administered by the Soviet Union. During this period nearly all the vineyards and winemaking was consolidated into the state’s hands; giant cooperatives dominated the landscape and all small, quality winemaking basically disappeared.

There’s your big picture, your short history, I guess.

If you want more on Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen, you can find some big-picture, sophisticated and questionably insightful general words about the region here, in our award-winning essay: “So ya wanna know about Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen, eh?” coming soon! There are some maps and photographs too, so you don’t really have to read anything if you don’t want to.

If you’d rather just hear about our heroes, Konni & Evi, well, stay here.

Konrad Buddress – we can call him “Konni” henceforth – was born in Saxony in 1994, not from a winemaking family. Growing up, to earn some extra cash, he helped a winemaker who lived nearby and he found he really liked it, this winemaking thing. He was only twelve at the time, so it wasn’t about the wine, it was about the bigger picture. Like, how in the hell did these plants grow on this rocky soil? And the soil influenced the flavor of the wine? And the wine came about from letting the grape juice do what?

It was nature, biology, chemistry, myth and magic all wrapped up into one beautiful and ridiculous package. He was hooked.

All the learning and studying and training and apprenticing stuff took him to Bad Kreuznach (Nahe), Würzberg (Franconia), New Zealand and Austria. In Würzberg he met Eva-Maria Wehner – we can call her “Evi” henceforth – and they fell in love.

In the end, it was an advertisement for a small parcel of a vineyard for sale in Saale-Unstrut – about 3,000 square meters, not even one-third of a hectare, 9,000 square feet of soil – that brought them both to Saale-Unstrut.

What’s important is not the size (small), but the vine age (very old).

This specific parcel, just outside of Karsdorf and south of the Grand Cru site Hohe Gräte, was planted in 1933 at a ridiculously high density, at somewhere around 10,500 vines per hectare. This is the preindustrial texture of viticulture, making no concessions for machines, tractors. Here was a site scaled for a human to work in. And this stood into stark contrast to the vineyards planted during the GDR, where every concession was made to the machine.

And that’s all that Konni & Evi wanted to do, work these older vineyards, as humans. They started; it was 2016.

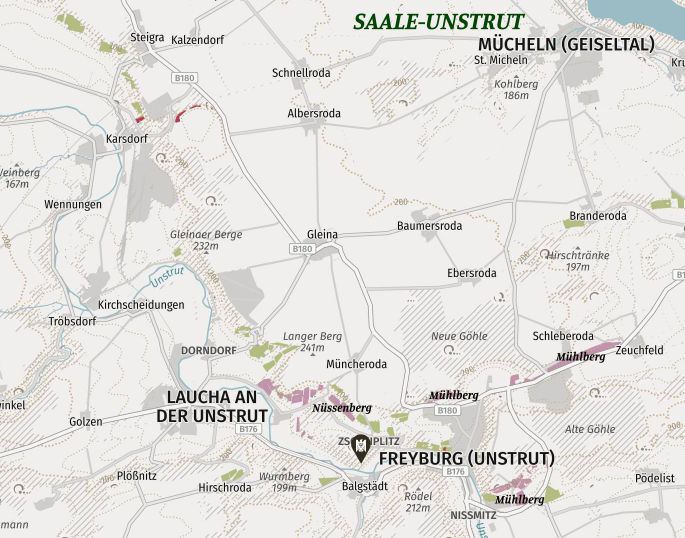

In the last five years they have managed to gather about 3.5 hectares worth of vines; their vision is to stop at around 4 to 5 hectares. A humanely scaled winery. That said, John and I spent hours – and I do mean hours – driving from small old-vine parcel to small old-vine parcel. Konni & Evi’s collection of vineyards and parcels resembles a patchwork quilt of soul; a bunch of gems scattered in this tiny region just west of Leipzig.

From the eastern-most to the western-most parcel, we’re only talking about 30 kilometers. Click on the map above and to the right to enlarge it, and you can see the general area. They have tiny parcels in the Mühlberg (on the right side of the map, their parcels are just east of Freyberg, under the “Unstrut” in parenthesis) to Schweigenberg (a very famous site; on our map their parcel is just above the word “Freyberg”) to just outside of Karsdorf (their first buy) all the way north and west to Steigra (the Hahnenberge).

Konni loves his vineyards. Our tour took the better part of a day and Konni must have smoked, conservatively, 8,000 cigarettes. Or, another possibility: It was the same cigarette, but it was so damn windy he just had to relight the cigarette 8,000 times to burn it down. Neither John nor I are 100% sure either way.

Konni & Evi are farming each and every parcel organically and biodynamically. If there was an Oscar or a Grammy or some prestigious award given for “heroic winemaking in the face of outrageous obscurity,” I would submit this young couple.

For harvest, as you can likely guess, everything is done by hand. In selecting the moment for harvest, everything is done by taste. Konni said to me: “I don’t want to know what the exact ripeness is, what the measurements are, because then I’d be unsure!” But what they are seeking is that very moment when the sugars in the grape are just overtaking the acidity. It’s a very specific moment.

However, for our palates, especially our American palates bathing in sunshine and brix, it is a more cutting, acid-driven style. These are razor-sharp wines that can clock in, bone dry, at under 10%, though most are between 10 and 11% abv. When Konni does measure the must, he says the Silvaners read at about 70 to 75 Oechsle – never more than 80. The acids, again in the must (you lose some degrees through fermentation), can push 11 grams per liter. This is a lot.

They use a simple basket press; it can only process about 600 liters at a time. Press times are normally between 20 and 24 hours, just so you have a sense of the process here. Or at least, at the very vaguest level, you have a sense of how human this all is; how hard it all is.

Even though they will normally do a two to five-day pre-press maceration, the juice from the basket press comes out so clean, they might have to scoop out some lees from the press to put in the barrels. They want the lees in there to help with the natural fermentation and to cultivate reduction, which they want to some degree.

After fermentation, if they find that a barrel is too reductive, they may decide not to top it up. With the Silvaners especially, a flor may develop – the yeast that forms on the surface of a wine, most famously used in Spain’s Jerez. Konni muses that this happens because the alcohols are so low in the wine, though he feels like something about Silvaner lends itself to this flor. The Portugieser barrels, also exceedingly low in alcohol, will seldom develop this flor.

It is a fascinating play of reduction and oxidation: of going inward while pulling outward.

I genuinely have no idea how to make sense of any of this, though it strikes me as beautiful. I think we have to concede, it is an artful élevage.

To make things even cooler, Konni and Evi use, exclusively, very dense oak barrels made with wood from the Harz, a forest about an hour north of their vineyards. The barrels are made by the last cooper in Saale-Unstrut, a man by the name of Carsten Romberg. They have a variety of sizes, from 200 up to 600 liters. (As far as I can tell, they are the only estate in Germany not to have any old DRC barrels.)

In the end, there will be one bottle of Konni & Evi in the United States for every six words I have written in this essay alone. They will not be easy to find, nor will they be inexpensive. But they are so worth it: the dizzying complexity and fine-ness of them all, as if Albrecht Dürer himself had etched these wines out of the Saale-Unstrut limestone.

We first tasted their wines in 2018. We wanted them so bad we went to visit them in Saale-Unstrut in 2019, just after the birth of their first daughter. We went to the 51st parallel for Konni & Evi. Now, two years later, after ravaging frosts, the joyous birth of their second daughter, the acquisition of a few new parcels, the hardship of tariffs, a global pandemic… the wines have finally arrived.

Good lord, at this point, it’s very possible I have written ten words for every bottle that will arrive. But these wines will be cherished.