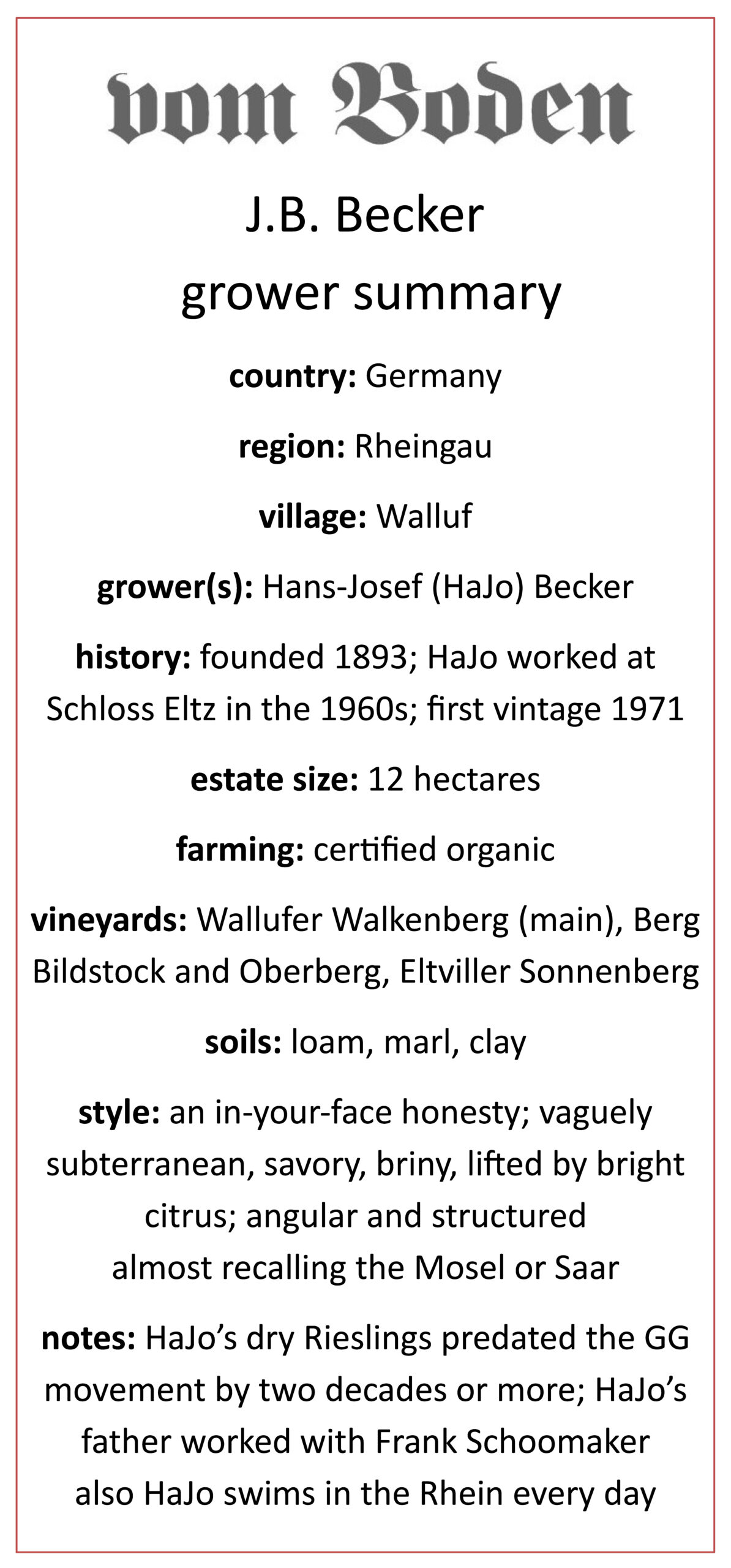

These wines taste like NOTHING else coming out of the Rheingau and Hans-Josef Becker just doesn’t give a ****.

Istruggled with a more elegant way of introducing this estate, some poignant lines contrasting the manicured lawns of the aristocratic estates with the dirty-fingered, weathered-skin, mess-of-a-tasting-room aesthetic at J.B. Becker.

Yet Hans-Josef’s (call him “HaJo”) winemaking has less to do with a condemnation or critique of the noble establishment (even if it deserves either or both) and more to do with a vision that is so singular and steadfast that it feels totally irrelevant whether you or I or anyone thinks Becker’s “aesthetic” is genius or folly. It just is.

The wines have an in-your-face, love-it-or-hate-it sensibility. They are unfailingly honest. They present a bizarre vocabulary: dried earth and rocks, herbs, something vaguely subterranean, a savory, briny, smoky atmosphere that slowly reveals fine layers of bright citrus. For all this depth and mysteriousness, Becker’s white wines are like Becker himself: angular, tensile with awkward elbows and muscle and sinew pulled tightly over a lean frame. They flaunt a rather prominent acidity that recalls the more nervy wines of the Mosel, Saar and Ruwer, though there is a weight, a density that speaks of the Rheingau. They seem to have more to do with great Chablis than with what we often think of as German Riesling.

The overall effect, one must say, is bewildering and inspiring. Becker seems to relish the paradox. If there is any grand system here, it is inscrutable.

Consider, on the one hand, that Becker (and his father before him) has worked the vineyards organically for many, many years (they have been certified since 2011). On the other hand, this rather important fact is mentioned exactly nowhere so far as I can tell. Not on the labels, not at the estate. HaJo mentioned it to me exactly once, almost as an aside. The life of the vineyard, at all levels, is profoundly important to Becker and he thinks about it deeply. He just doesn’t talk about it much.

Becker is a strong advocate of wild-yeast fermentations. This practice puts the graying wild-statesman of German winemaking right next to the young German hipster-growers, as obsessed with natural yeasts as anything else. On the other hand, since vintage 2003 Becker has bottled his wine with glass closures, which of course alienates him from this same population.

Becker prefers to use pressurized tanks for fermentation, relishing a quick, warm fermentation (a similar method is used at places like J.J. Prüm, Keller, etc). Then he racks the juice into the traditional barrels of the Rheingau for at least two years of barrel age before bottling. In other words: Gun the shit out of it and then slam on the breaks and wait out all the others.

Even with these very long élevages, Becker seems to release wines willy-nilly – he keeps older vintages around because, in a way, the wines demand it. I have had plenty of Kabinett Trockens at well over 20 years of age and they are gossamer and fine and sprightly and profound.

I’m not sure anyone really knows what to make of HaJo. Certainly there are no easy answers to anything at Becker. So here are the facts.

The estate was founded in 1893 by HaJo’s grandfather, Jean Baptiste Becker. He was a cooper and began accumulating some vineyards and voila, he started a winery. J.B. Becker died in 1944 at the age of 73. So the story goes, he saw a young child drowning in the Rhein River, yet even at his advanced age he jumped in, saved the child, then had a heart attack and died. There is a moving letter about the incident in the tasting room. Suffice it to say HaJo comes from a long line of bad asses. Becker’s father Josef grew the estate and in the 1930s befriended a young importer by the name of Frank Schoonmaker. They became good friends and Becker acted as Schoonmaker’s consultant and consolidator for some time.

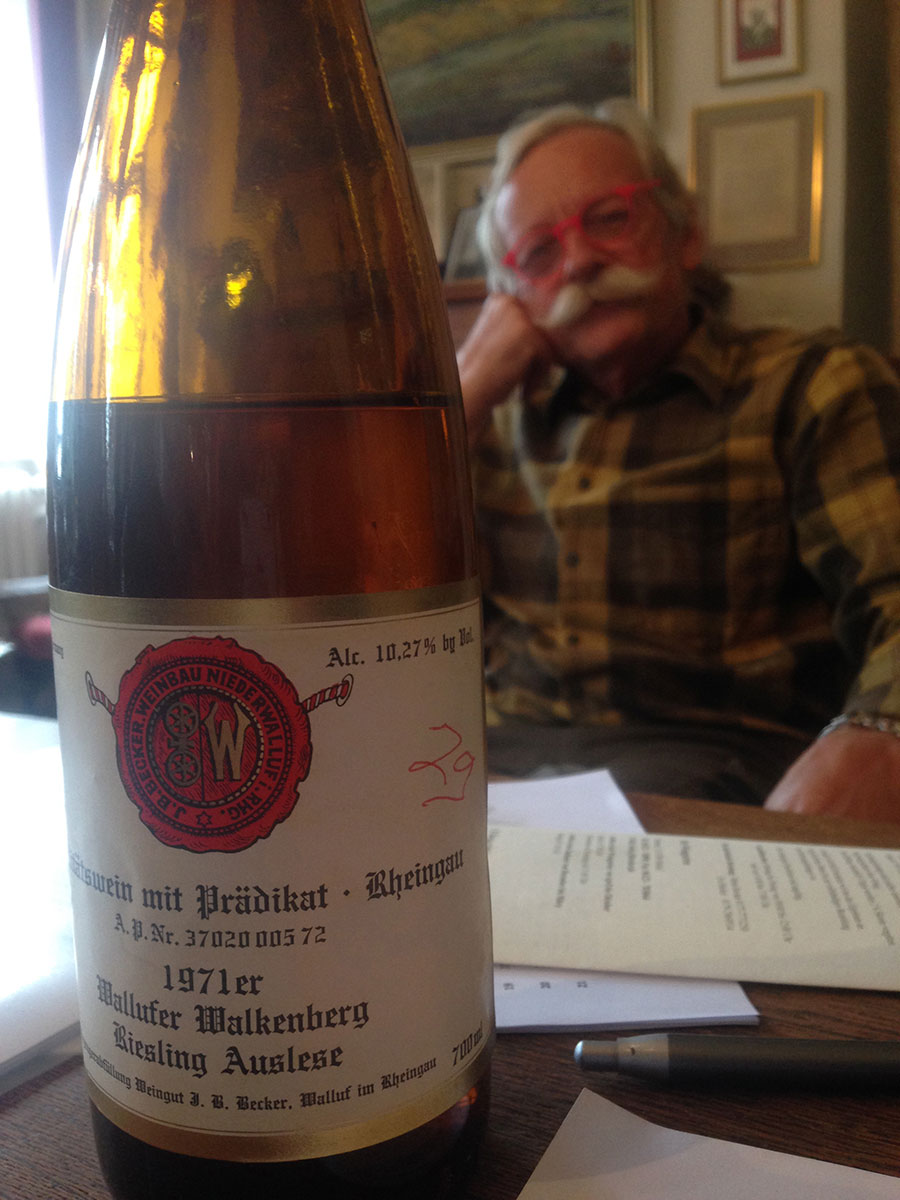

Hajo himself went to Geisenheim in the 1960s and did all that proper education stuff but as he tells it, his great revelation came in the cellars of Schloss Eltz in the early 1960s. Schloss Eltz, it should be said, made some of the greatest wines of the Rheingau from the 1950s through the 70s. The wines are just epic, if rather unknown these days because the estate sold its land in the 1980s. In any event, Becker was studying with the cellar master at Eltz, a gentleman by the name of Hermann Neuser, in the early 1960s and this is where he first began tasting dry Rieslings, fresh from the cask in the cellar… before any süssreserve was added. The wines were a revelation to him and when he took over the family estate with vintage 1971, he began focusing heavily on dry Rieslings.

I remember HaJo narrating this to me one time and, with bated breath, I asked: “Well, what happened when you switched to dry winemaking?” HaJo, never one for much talking, simply said: “I lost all my customers.” And then he took another sip of wine.

Now, more than 50 years later, Becker’s glorious wines are finally getting the attention and the praise they deserve. So far as I can tell he anticipated the dry wine movement in the Rheingau a few decades before anyone else. I asked him how all the new-found attention made him feel. He said, rather quietly and matter-of-factly, “it’s nice.”

Then he took another sip of wine.

Above check out our tour of Becker’s vineyards. We begin with the two most important historical regions, at least for the export markets, the Mosel and Rheingau in comparison. These are the regions that have largely defined German wine for the 20th century. The Mosel was light and mineral; the Rheingau was deep and powerful. The two regions are VERY different and you can see a bit of the scale here, the Mosel is larger at around 9,000 hectares (including the Saar and Ruwer) while the Rheingau is 1/3rd of the size only around 3,000 hectares.

As we zoom in on the Rheingau as a whole you’ll note Becker is in the far eastern side of the Rheingau – Walluf. Because this village never had any castles or nobility it was largely overlooked – but it has a great set of vineyards, highlighted by the Walkenberg. Historically, most of the famous estates and vineyards were on the western and central parts of the Rheingau.

Where the vom Boden square is with the words “JB Becker” are is the estate and wine bar on the Rhein on the edge of Walluf.

Moving to the vineyards the Walkenberg is Becker’s greatest site; it is also his largest site with holdings around 5ha. He is able to edit his pickings and farming here – to shape the wines he wants for the style of the domaine year in and year out. In many vintages Becker can make a Kabinett Trocken, Spätlese Trocken and Auslese Trocken from the Walkenberg. Next up is the Oberberg and Bildstock which tend to be the coolest; oftentimes they are made into Kabinetts with a bit of residual sugar because of the cool sites and more prominent acidities. The Rödchen is a bit of a mystery; it is a cooler site in theory but because of the small parcel he has, he comes here last and oftentimes make a riper Auslese out of it. This is a touch counterintuitive as you’d think a lighter Prädikatwein would come from a cooler parcel. Finally, the Rheingberg is the outlier – it’s the only vineyard of the Rheingau that actually goes right up to the Rheingau. Because of the warmth and the clay, there is mostly Pinot Noir planted here.