The “other” Nahe?

Talk with any – and we mean any – winemaker in the Nahe and she is likely to quickly turn the conversation to the geological complexity of the soils here.

“The most diverse soils in Germany,” he will say.

And it’s true. Scattered over this relatively small appellation (the Nahe is about 4,000 hectares, about half the size of the Moselle and a seventh of the size of the Rheinhessen or Pfalz) there is a kaleidoscopic array of soils, from slate and sandstone to quartzite and other volcanic soils.

Yet, for all this wild complexity, in the U.S. at least, we have three estates that have more or less defined the entirety of the Nahe for the last twenty-plus years: Dönnhoff, Emrich-Schönleber and Schäfer-Fröhlich. And while they have their stylistic differences, all of them more or less work in the canon as defined by the VDP.

That’s curious, isn’t it?

It’s like having an entire orchestra’s worth of musicians – French horn, bassoon, piccolo and timpani included – and only listening to three of the violins. Or, to use the analogy a bit more accurately, it’s like having this amazing symphony, but only ever playing Mozart. Sometimes the rather bizarre Erik Satie is nice, you know?

A deeper exploration of this place is long past due. A deeper exploration of the basic tenents of traditional German winemaking here is long past due.

What the **** else can the Nahe do? What else can it taste like?

This questioning is, I think, taking place with more rigor and seriousness (as well as with more joy and excitement) at Glow Glow than nearly any other estate in the Nahe that we have tasted at, have visited, or that we can think of frankly. (And, for the historical record, we have spent a lot of time tasting, visiting and thinking about the wines of the Nahe.)

But let me explain in more detail.

After questioning many of the basic assumptions of their traditional family estate, daughter Pauline and son Carl Baumberger began in 2019 to experiment with a micro-production line of wines they would eventually call Glow Glow. It all began with two half-barrels.

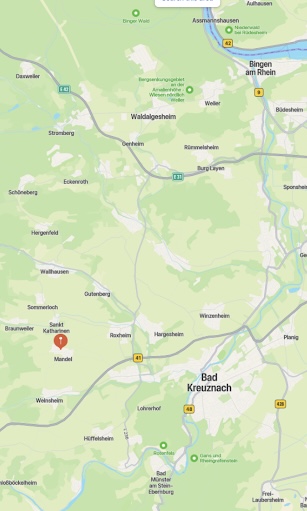

It was (and remains) a focused project, humble in scale, using fruit from the family’s vineyards in the tiny village of Mandel, nestled into one of the many overlooked and largely unknown side valleys of the Nahe. To give you some bearings, Bad Kreuznach, the biggest and most important city of the Nahe, is only 15 minutes east. Tim Fröhlich’s Bockenau, another at-the-time unknown village, is only about ten minutes due west.

The kids had the very earnest desire to simply see what would happen if they employed organic farming, relied only on natural fermentations, combined grapes with more creativity and freedom, and bottled the wines unfiltered and with no sulfur.

For your average wine drinker here in the 2020ers, none of this is particularly new or noteworthy.

Yet two important facts remain.

First, this was one of the first “natural wine” projects in the Nahe, which is interesting when you consider that even in the rather staid and traditional Moselle, there exists a long list of contrarians and rebels going back three decades at least, from Trossen and Stein, to Thorsten Melsheimer and now to an ever-growing group of younger-generation growers just beginning their careers including Philip Lardot, Julien Renard, and Jakob Tennstedt to name only our favorites.

Second, and this is what piqued our interest, the wines were, from the very first vintage, simply superb. They were delicate, fine like linen, buoyant and compact and minimal (the wines feel full at even 10% alcohol) to a degree that even the still wines felt somehow effervescent. Most importantly, the wines were implacably clear, almost shimmering. They were clean. They were a joy to drink. They felt like beverages made from the earth, filtered through soil and stone.

Wine, for sure, but also something more than wine in their ease?

These are bottles that are so irrefutably delicious and refreshing, so poised and natural, that you can’t deny them. Which makes sense, I think, when you consider the rather cold Nahe – especially in these deeper side-valleys (here the Schäfer-Fröhlich / Bockenau connection is very valid and insightful) – in the context of the Saar, which I do. (Read more about this theme in my new book, which you can purchase here.)

The point, however, is that both regions – the Nahe and the Saar – are very cold and this cold, in essence, gives the wines here a natural restraint, a taut, compact precision, an energy… a glow.

Glow Glow quickly went cult in Germany, marrying the punk-rock, kumbaya vibes of the natural wine world with bottles that were actually clean, balanced, representative of variety and place… and easy as hell to drink.

Now, keep in mind John and I are both curmudgeonly old-school German-wine lovers who in good faith still drink Spätlese and talk about people in their late 30s as kids. We are most obviously not in the slightest bit cool.

As such, we look at anything cool with some trepidation. At some basic and probably shallow level, I don’t know if we thought of ourselves as quite hip enough to import wines called Glow Glow. (We will visit why our opinion here has changed, below.)

But then we tasted the wines.

And then there were Pauline and Carl just standing there smiling at us as we stood there smiling at them. Both of them somehow seemed to, well, glow. I have met few people (and then later, after we met the family, few families) who simply effuse goodness, sincerity, honesty… to a degree where it almost seems like a vulnerability, maybe a naiveite one could exploit – until you realize that it’s actually a profound strength.

I can’t explain it exactly, but it’s as if their complete transparency – as to what they want to do and how they want to do it – forces you to be equally as transparent and honest.

I can’t explain it exactly, but it’s as if their complete transparency – as to what they want to do and how they want to do it – forces you to be equally as transparent and honest.

This is where, I suppose, my appreciation of the “Glow Glow” moniker and philosophy feels now less marketing savvy, less polished for easy sales, and more just a genuine expression of the project – or just a genuine expression of the family, because this is in fact what Glow Glow now is: a complete family affair.

In my near-twenty years of floating around the wine world, I have personally never seen a situation unfold in this way: The children’s requests for serious change at an estate over 150 years old has been met not with opposition, or even passive acceptance, but with absolute agreement among the mother, daughter, son and father.

The entire family has a radical openness, a courage the likes of which I have personally never seen.

And so the real story here is not of the kids rebelling, of a splintering of the family estate, of two paths. The real story is not classic versus natural wines or some tired generational drama.

The real story is of a family growing, together.

But this is also a story being written, in real-time, as a family, at their big beautiful dinner table under the willow tree in a village named Mandel.

What does the future hold? We have no idea. But we’re just happy to be able to visit and to, occasionally, have a seat at the table.