The estate known as Enderle and Moll is really just a tiny cellar, a basket press, a few hectares of old vines and a hell of a lot of buzz.

Shit – even the venerable Jancis Robinson has called them “cult.”

In Germany many insiders consider Enderle & Moll the country’s single greatest producer of Pinot Noir. That’s a wild claim to be sure, but then you taste the wines and you think to yourself, “…yeah, alright, well maybe…”

The wines are that compelling.

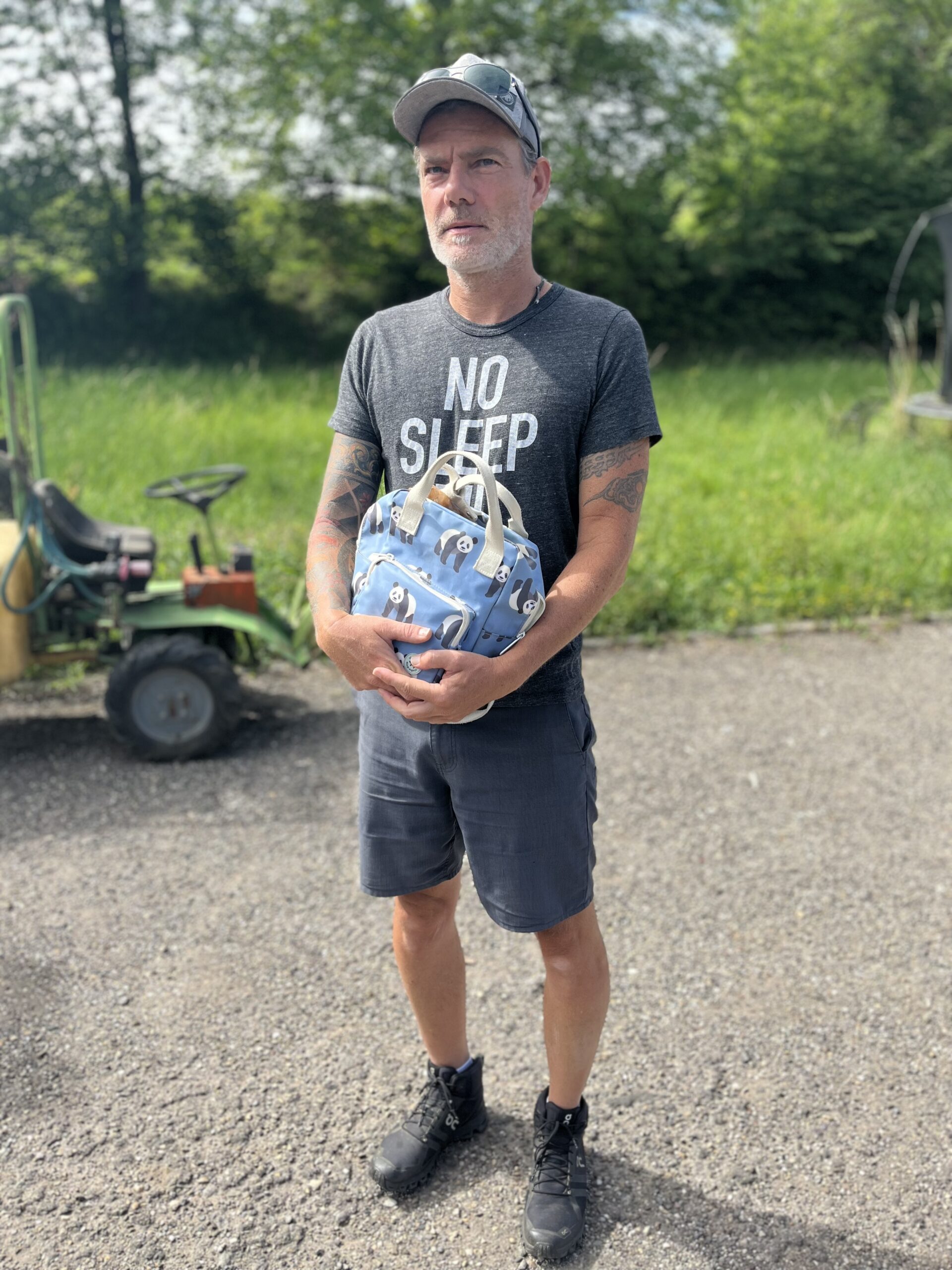

What you can say with certainty is that Florian Moll, along with his partner Géraldine, fly in the face of just about every conventional estate in Baden.

Sure, the landscape has changed a lot in the last 15 years, with producers like Hendrik Möbitz, Shelter and Wasenhaus. But when they started in 2007, what they were doing was for all intents and purposes blasphemy. Truly, it’s hard to emphasize how contrarian (and even confrontational) their vineyard and cellar work appeared to the powerful coops of the region, to say nothing of the “famous” estates who at the time were busy pursuing efficiency, ripeness, size, alcohol and, yes, new oak, with abandon.

From the beginning, the focus here was not on ripeness, but on the age and quality of the vineyard. They work with very old vines. In fact their vines are among the oldest Pinot Noir vines in Baden. They farm all the vineyards organically and biodynamically. Absolutely everything is done by hand in the vineyards and in the cellar. They were among the first to actually request used barrels, seeking a more delicate élevage. Although every winery in Germany now claims to somehow have a DRC barrel or two, Enderle & Moll were among the first to realize that the provenance of the barrels mattered, a lot, and they began, famously, with used Dujac barrels, though of course now they source barrels from around Burgundy. The wines are bottled unfined and unfiltered.

The Pinot Noirs are famously light, bright, energetic, detailed, ethereal, satiny, even if they can be broad-shouldered and powerful in a sneaky sort of way. Thus the mystery, the beauty and yes, all the damn fuss. At this point it’s said so often it’s beyond trite, but here we go: If you appreciate Burgundy these wines are worth checking out. Not because they taste like Burgundy, they don’t, but because they share a similar aesthetic of lightness matched to intensity, filtered through soil.

Depending on the vintage, the estate can make up to four “Grand Crus.” First, there are the two terroir-specific Pinots: a wine from limestone called “Muschelkalk” and a bottling from colored sandstone called “Buntsandstein.” Then, there is a tiny colored sandstone parcel they took over from this older lady named Ida; the barrels always had a unique quality to them, so when they can, they will bottle a “Buntsandstein Ida,” honoring this small parcel. Finally, if the vintage allows, they may bottle a “Pinot a Trois,” which is nothing more (or less) than the top grapes from all three sites. In 2018 they made good quantities of all of these wines; in 2019 they could only make the Grand Cru “Muschelkalk.” So it goes.

The “Liaison,” a sort of middle-wine-premier-cru-style, is a blend from younger vines in the Grand Cru sites. “Young,” it should be said, at around 45 years of age, which the French will often call “vieilles vignes.” The “Basis” is from the youngest vines, around 30 years old.

While the red wines have established the reputation of the estate, the white wines have become very sought out as well. The reason honestly has less to do with the wines – they have always been great – and more to do with the fact that this style of white winemaking is very much in vogue. Yes, please know that Enderle & Moll made “orange,” skin-contact white wines before most other wineries on earth did (with the possible exception of Friuli and a few other places in eastern Europe) for the sole reason they are red-wine specialists and, well, skin-contact is just what they do. To add insult to injury, Enderle & Moll also ended up putting the wines in clear bottles and didn’t filter them, again, just because that’s how they did it. For the first 10 years the wines had a good following and they sold through well enough. But now, of course, without meaning to they find themselves at the center of this movement. The biggest difference, it seems to me, is just the labels are pretty traditional, the wines are clearer and have more acid than most, and they are about 50% the price of most of the others at the same level. For me, they sort of remind me of Clos Roche Blanche; they just do their thing, make really, really good wines. If they aren’t as hip or as cool as some of the other labels, that’s ok. The wines are fairly priced and your average person can afford to buy them and drink them and enjoy them.

And then, if it turns out like it did with me and all my Clos Roche Blanche, you take it all for granted, how truly special and great this “everyday” wine is, was… and you wonder, years later, why you didn’t recognize the dazzling humility of the wines, of the estate, of the people. I guess the only difference is with Enderle & Moll you can still get the wines… for now.