clouds over Piesport

introduction | Einleitung

Early in my career, not knowing what I know now, I missed out on the racy vintages like 2004 and 2008. They were, well, bracing in their youth. I loved their cut and buoyancy; it was like drinking directly from a mountain stream while sticking your finger into an electrical socket. I discovered I enjoyed that sensation, to be honest.

But I just didn’t have the experience to know that the toughness of these wines – the very thing that made them hard to understand in youth – was exactly what they would need to develop into the following decades and remain fresh.

Maybe I didn’t really trust myself? And the riper vintages of 2005 and 2007 were getting all the attention, all the love. What the hell did I know?

The first Rieslingfeier that was held in New York in 2013 was a revelation; of the fifty-some people in the room where it happened, I’d say thirty commented on how absolutely stunning the 2008ers were. I was floored.

Since that moment, I’ve been buying as many 2008ers as I could. I’ve also gone further back into the cold box, when I could, to find all the misunderstood vintages: 2004ers, 2002ers, 1998ers, 1996ers, etc.

All this to say, I’m not going to make this mistake again.

Vintage 2021 is one of the first truly cool vintages in about a decade; it is a piquant middle-finger to our age of climate change and ubiquitous ripeness. This vintage is a time machine to a colder time. This vintage is fresh spring peas after a decade or two of foie gras.

Das a Mosel boat cruise

WARNING: I write the following sentence as a German wine fanatic and collector and not as an importer: I personally am going very deep in 2021. Maybe such an admission – putting your money where your mouth is, as it were – is meaningful to you personally, maybe it isn’t. I’m just telling you a fact.

As an importer, however, I want to write something grander, a bit more philosophical and heady in that vaguely impactful way.

So here it is: I think 2021 will prove to be one of the most defining, most consequential vintages of our era.

Here’s what I mean.

I think this is the vintage where many of the ideas and concepts that we were only just barely still hanging onto, frameworks hardly intact, threadbare really, will finally snap, break apart – shatter into a million pieces.

I think 2021 will help us see, almost as if with new eyes, that the way we thought about German wine is no longer the way we must think about German wine. As but one example: Vintage 2021, I think, will not only mark the moment we realize that the Kabinett is in no way a “basic” wine, I think it is the moment that the Kabinett will really take its place as one of the greatest, most singular and unique expressions of German wine culture. Obviously those in the know have understood this for many years. Yet the market is beginning to acknowledge this as well. For the last two years Egon Müller’s auction Kabinett has been more expensive than his auction Spätlese. In the 2021 Keller vintage report, Klaus Peter and Julia Keller describe the Kabinett as “the diamonds of German wine culture.”

I believe this is the watershed moment: Going forward we will see Kabinetts priced at the same levels or even higher than the other Prädikats. Not that far in the future, I suspect, they will be among the most expensive, and perhaps the rarest, of the Prädikat Rieslings.

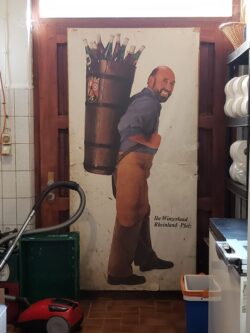

Ihr Winzerland

I go into this in more detail below (see the chapter below entitled “the wines | die Weine”) but I think there is a good amount of logic to state quite plainly that the Kabinetts of 2021 perhaps represent the greatest Kabinetts ever made in the history of this genre. (Incidentally, vintage 2021 turns out to be the 50th anniversary of the 1971 wine law that created the Kabinett, so that’s a nice coincidence.) Before you freak out that I’m hyping something without reason or caution, read the chapter; this is a philosophical argument, not one based on any grand tasting or even my limited tastings.

Yet for all this, in another way vintage 2021 is really just a sentimental vintage. What we’re celebrating with this vintage is the way it used to be. The serious differences between 2021 and, let’s say, the cool vintages of our century (2002, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2013 and 2017) are perhaps not so grand.

So what’s changed you ask?

We have changed.

We are different; our expectations are different. We now know, I think, that ripeness will no longer be the true challenge – balance will. And so now, the gifts that we are given in these cooler vintages – the generosity of restraint, the thrill of balance, the wispy dance of true delicacy, the energy of acidity – perhaps now we are ready to celebrate these characteristics with the grandeur and pomp once reserved only for ripeness and power.

What we ignored in the past because it was too “average,” maybe we will now be forced to acknowledge as truly spectacular… and perhaps even rare as we enter this new age?

I think vintage 2021 may be the perfect vintage at the perfect moment.

the weather | das Wetter

The few preliminary vintage reports I’ve read I find maddening. The rain, the rain, the rain, the rain – as if any of this tells you anything, really.

Maybe it’s a matter of perspective?

If we’re gonna talk big-picture generalities, the truth is that after three very hot and very dry years, the rain was a godsend for the environment. The forests, the fields and crops, the reserves of ground water desperately needed this rainfall. In truth, even the torrential downpours of 2021 weren’t enough; the landscape needed, and needs, more.

It was the pacing of this rain that was disastrous. Climate change is revealing a new landscape that swings wildly between extremes, from drought to floods with a jarring snap. The deluges of June and July culminated in the devastating floods in Germany’s Ahr Valley in July of 2021; I think many people are still trying to come to terms with what happened, the shock and magnitude of this disaster.

Ulli Stein on das Wetter

From the perspective of the vines, the rains of June and July were, at first, a welcome relief. Keller called the early rains of June “a blessing;” most of the growers spoke in similar tones. It was the large amounts of rain, the intermittent, unpredictable pacing which proved to be a complicated and maddening gauntlet for growers to navigate. The windows of dry weather to work in the vineyards were very short and it was impossible, of course, to know what the future held. If you took advantage of a dry Monday to spray the vineyards and it rained on Tuesday, well, there was a lot of work for nothing. For organic growers especially who spray only very limited topical treatments (meaning their effectiveness is predicated on the treatments remaining on leaves and shoots), 2021 was very, very difficult. The rain simply washed away the treatments. Many organic growers who would normally only spray six or eight times a year had to spray fifteen or eighteen or more times. And still, the fungal pressure from Peronospera (downy mildew), black rot and botrytis was intense.

There are a few things, however, to keep in mind when thinking about the rain and fungal pressure in the context of 2021. The first thing to be aware of is that all of this fungal pressure, so early on in the year, is a factor that influenced the yields of the vines and not the style nor quality of the wines – at least not in the direct way you might be thinking. In other words, in June and July the berries and clusters are quite small and dense. They are compact and weighty, more like tiny green ball bearings than grapes in the way we probably think of them, all soft and water-filled. When the bunches and leaves and shoots are infected at a high level, the clusters must be physically removed – sometimes they are cut and left on the ground, sometimes they are taken completely out of the vineyards so as to not influence the vines and shoots any further. In the end, none of this is a matter of “sorting” and picking only the clean grapes in a way that might happen with rains closer to or during harvest. This is simply a matter of cutting away entire clusters of grapes. Not to minimize what is a wildly important financial factor for growers (how much “product” you end up with at the end of the season), but the early fungal pressure in 2021 resulted in more a tragedy of quantity, without really influencing quality.

The second thing to keep in mind is this sage truism: most shit is very complicated – like unfathomably complicated. As anyone who’s read any vintage report I’ve ever written, you’ll gather I f***ing loathe them. I especially hate simplistic overviews of the weather; the sort of which I’m doing right now.

Live view of John writing this vintage report while Stephen drinks beer

Individual growers, yes, should be able to recount their year, their experiences. But for a critic – or worse yet an importer (gross) – to try and summarize an entire country, or region, well, shame on John, who actually writes all of these reports.

I visited close to forty growers in August of 2021, another thirty this March and have emailed, texted and spoken with another twenty. They’re not all unique growers – people I saw in August I probably saw again in March – but I’d guess I have heard somewhere in the neighborhood of fifty different narratives, fifty different realities. There is no one story for any vintage, period.

With that elegant introduction, here’s a semi-nonsensical geographical summary, an admittedly vague and general accounting of a complex reality.

The middle Mosel did get a lot of rain and the organic growers had problems, there is no doubt. I tasted together with Weiser-Künstler and Vollenweider. They both truly love their wines in 2021 – stylistically it is a superb, classic Mosel vintage – but they also made no effort to cover up the financial, physical and emotional toll this vintage took. The vintage was just an unwinnable fight for organic growers. Here’s the sobering reality of 2021 for many growers: literally half the amount of wine with twice the amount of work and expense. If the top wines of 2021 are absolutely bonkers – and they are – this doesn’t exactly negate the realities of the vintage.

For all the growers in the Mosel I spoke to, yields were down, significantly. Weiser-Künstler and Vollenweider were down to 25 hectoliters per hectare (hl/ha) on average. I spoke with Kirk Wille, the President of Loosen Brothers USA, and he said Von Schubert only brought in around 30 hl/ha. Ludes, Julian Haart and Stein were all around, or just under 40 hl/ha. I think most of these growers would want to be at 50 or 60 in a normal year, so you do the math.

Curiously, the Saar seemed to not have been hit quite as badly. I met with a number of growers in the valley and the basic narrative seemed relatively consistent: Yes there was a lot of rain and higher-than-normal fungal pressure, but it wasn’t as devastating as in the Mosel. Some of this must be due to the general landscape of the Saar. First, many of the top vineyards are not close to the river and therefore perhaps have a bit less pressure from humidity? Second, the Saar in general is a much more open and wind-swept landscape; the gusts and general exposure perhaps helped to dry things out more quickly, lessening the pressure at least somewhat?

I visited with both Frank Schönleber (Emrich-Schönleber) and Tim Fröhlich (Schäfer-Fröhlich) in the Nahe. Both said the rains weren’t really a problem for them; both of them reported yields very close to normal. The same general story seems to be case in the Rheinhessen. Both Keller and Seehof had lower-than-normal yields, but still quite good.

Es Gab Sie Nichts

The Pfalz is a big place and I don’t have that many growers there to get a real sense of what happened. The Brands and Andreas Durst benefitted from being in something of a rain shadow. And while their vineyards are hardly the steep cliffs of the Mosel, most of them do have some incline and so drainage was better than in many of the Pfalz vineyards which can be quite flat. All in all it was a lot of work, as organic wineries they had to spray a lot, but it wasn’t devastating – the yields are lower than normal, but not bad. There were stories of a lot of rain-soaked vineyards much too wet to drive through with tractors; one grower showed me a photo of a friend’s vineyard with a tractor stuck in the vineyard, half covered by the water of a puddle-pond that had developed. For the larger estates that rely heavily on mechanical agriculture, the rains of 2021 were a big problem. Again, as I’ve said over and over again, size matters; small growers simply have a profound advantage in challenging vintages. You will taste this too in vintage 2021.

As with the Brands in the Pfalz, it was a similar situation for Roterfaden and Beurer in Swabia; a tricky vintage that was a lot of work, but not bad. For reasons Jochen Beurer really didn’t understand, his village just didn’t get that much rain – the vineyards were really healthy in 2021. A touch further south and west, into Baden things were more mixed: some places really suffered with the rains, some less. Shelter had fungal pressure and they lost about 30%, which in the end isn’t too bad. Hans-Bert and Silke, the husband-and-wife team at Shelter, pointed out that while the lower yields hurt a bit financially, in other ways these lower yields were absolutely critical for 2021.

And this – the play of ripeness versus yield – this is where we actually get to the heart of vintage 2021, thank you Hans-Bert and Silke. It is only now, having dealt with the distractions of the rains, that we come to what is actually the most important meta-theme for 2021: the ripeness and the pacing of the vintage versus the yields.

For one of the few times in my career, the growers could compare the timing of flowering and the timing of the harvest with vintages from the 1980s and 1990s. The flowering was late when compared to the most recent vintages, which is to say in the area of normal when looking at vintages from previous decades. While June and July were warm and wet, the late flowering meant that most growers were running well behind schedule in terms of ripeness – perhaps even alarmingly behind in terms of ripeness. And here we have a very important, yet less-discussed concern.

For most growers there was a hypothetical fork in the road during 2021; you could choose only one path.

One path we can call “the easy ripeness” path. Growers who took this path, reasoned something like this: “In this age of climate change, ripeness is no longer a problem. However, the rains are making us cut away lots of infected grapes, so if we want to have good yields at the end of the year, we need to keep as many clusters on the vines as possible. These high yields will slow down ripening, of course, but again, ripeness isn’t a problem for this new warmer Germany, right?”

Bats welcome here

The other path we can call “the high-wire dance.” Growers on this path would have posited this: “We’re still a cool-climate country; with ripeness levels as far behind schedule as they are, we need to reduce yields and focus the ripening – the limited energy of the vines – on fewer grapes. This is the only way we’re going to get truly ripe grapes.”

Two very different paths and a critical decision to make. The problem was this decision had to be made in June or early July, knowing full well the answer might not be totally evident until mid-August.

By mid-August, in any event, it was obvious that a cool-to-cold month had set in and indeed, ripeness in 2021 would be an issue. Those growers who decided to leave grapes and go for larger yields, they might have some problems. In fact, while the cool August laid the foundation for the profound aromatics and the bracing structures of the vintage, it also put a tremendous amount of pressure on September. If September wasn’t warm and dry and sunny, even for those growers that reduced yields (either because of the rains and fungal pressure or because of the cooler weather) the vintage might have turned out very, very differently.

As it were, September and October saved the vintage. September especially was warm and dry, which pushed the ripeness levels up slowly into the safe zones while the cool nights preserved the muscular acidities. For most growers, harvests of other, earlier-ripening varieties didn’t begin till mid-September; the Riesling harvest didn’t really begin until October, with the middle to end of October being something of the sweet spot. By the end of October or the first few days of November, vintage 2021 was over (with the exception of some ice wines made in December).

ripeness | die Reife

More than a few growers talk of the vintage 2021 as something like a quest, a gauntlet to survive – or perhaps more as a subtle message from nature that you had to divine, to read in the landscape itself. This was a vintage of hours and hours of hard, hard work in the vineyard, without question; but it was also a vintage of intuition and touch and feeling.

Clouds over Wintrich

One of my favorite German words might be appropriate here: Can you say “Fingerspitzengefühl?”

I knew you could.

Literally it translates to “the feeling in the tips of your fingers,” the closest English-language idiom might be “to have your finger on the pulse” though I think the word more speaks more to just having an almost innate sense of what is happening – a knowledge that is unconscious, instinctual, post- or non-verbal. (Curiously, Germans use the word Fingerspitzengefühl to describe the touch and feel that European soccer players have… using their feet, just throwing that out there.)

Back to wine: Yes, 2021 will prove to be a “winemaker’s vintage.” I’d consider less the question, “How much rain did the vineyard see in 2021?” and consider more this question: “Which winemaker did the vineyard see in 2021?” (There’s your buying advice for vintage 2021.)

It stands to reason that in vintage 2021 there is going to be not a small amount of slightly (or more than slightly?) underripe wine, from those growers who took “the easy ripeness” path in a vintage that simply didn’t provide easy ripeness. That said, with chaptalization and other cellar tricks, most of this wine is not going to be sour or tart as much as it will just be… boring – a touch dilute, placid, lifeless, nondescript. In a vintage that boasts a billion megawatts of kinetic energy, these wines will feel a shade tired – like someone yawning at a rave.

However, from those growers who made it through “the high-wire dance,” we are going to find wines with good to very-good ripeness levels. This is not a vintage of high-Prädikat wines – with random exceptions here and there, the vintage mainly tops out at Spätlesen and even those are pretty rare. The heart and soul of the vintage is clearly and obviously the myriad off-dries, Halbtrockens and Feinherbs and, yes, the holy Kabinetten. Yet before we get too deep into the levels of ripeness in 2021, we really should consider three other important factors: acidity, pH and dry extract.

The Scharzhofberg

In a way, the defining quality of 2021 is not the ripeness level per se (which are in fact stunningly average), but the corresponding acidity, pH and dry extract. It is these factors that are not average at all. These are the factors that truly that shape the feel, the balance, the pulse and life of the wines.

If ripeness is, say, the equivalent to the weight of a wine, these other factors shape the personality of the wine.

For vintage 2021, the acidities, in general, are strong; they are brisk, yellow- and green-toned jewels (in the best way), herbal and incisive. Yet the very low pH levels for many of the 2021ers mean that these tenacious acids feel even more lucid, more reverberating, longer, more present, more persistent.

On the other hand, the lower yields also mean the dry extracts are also very high in 2021; the uptake of minerals and especially potassium, was dramatic. These dry extracts act to buffer the intensity of the high acid and low pH combination.

This, in any event, is the rough outline, the architecture of 2021. Maybe some of you remember tasting the young 2010ers, or 2013ers, or even the 2017ers – the general feel of almost chewy wines, dense and palate-coating, yet also agile, dancing, electric. Maybe some of you even remember tasting the shocking, bracing quality of 2004ers and 2008ers, in their face-slapping briskness.

Yes people, it’s a similar vibe for 2021. We at vom Boden could not be more excited. Seriously.

the wines | die Weine

Kabinett

With all this background as our witch’s brew – this landscape of medium ripeness, riveting and incisive acidities – it’s hardly going to be too shocking to declare, as many have, that 2021 may be a simply perfect, perfect vintage for Kabinetts.

Here’s a little laundry list of various Kabinett-scenarios (in no particular order) that are so exciting I sometimes feel like I’m going to pee my pants, or my head is going to explode, or both:

Florian Lauer has made his first-ever Kabinett from the Schonfels vineyard, a spine-tingling site with 100-year-old ungrafted vines.

Julian Haart has made six different unique single-vineyard Kabinetts – because there is so little wine and he doesn’t think he’ll be able to do anything like this again anytime soon, they will be sold in a set.

Julian Ludes and his uncle Hermann have made six different Kabinetts (!) and Julian thinks they may be the greatest the estate has ever made; a few of these Kabinetts will be bottled in magnum (!!), one of these Kabinetts will be bottled in double-magnum (!!!).

Frühlingsplätzchen

Emrich-Schönleber has bottled a single-vineyard Kabinett from the Niederberg vineyard – an awesome site that you’ve likely never heard of but holy hell in five years you will know the name of this site very well. This will be the first-ever Kabinett from this site for the estate.

Klaus Peter and Julia Keller have made their first-ever Kabinetts from top parcels in the Kirchspiel and Abtserde, joining their already impressive roster which includes the two Roter Hang sites (Hipping and Pettenthal) as well as the Mosel site Schubertslay.

All our other Kabinett-friends will be at the party too for 2021: Weiser-Künstler and Vollenweider, Stein and Seehof (his Kabinett Morstein may be one of the greatest deals of the vintage). Hopefully you’ll make some new Kabinett-friends in 2021; Tim Fröhlich’s Felseneck Kabinett is, yes, a masterpiece. Sebastian Schäfer in the lower Nahe (Joh. Bapt. Schäfer) is making incredibly fresh Kabinetts that go down like mineral water. The Falkenstein Kabinetts are glorious; ditto Egon Müller (and for those that can find them, the Le Gallais Kabinett is stunning). I haven’t yet tasted the wines of Caroline Diel or Christoph Schaefer yet though I just can’t wait to see what they’ve shaped for the vintage. There is a lot to look forward to.

All of this Kabinett-talk leads me to the hypothetical I posited in the introduction: Could the Kabinetts of 2021 represent the greatest Kabinetts ever made? This is obviously a ridiculous proposition, on so many levels, but hear me out.

We’ve reviewed the details of the vintage, the weather conditions and the analytics of the resulting wines. It all seems like a very good, maybe even a super-great year for the Kabinett. Yet it’s impossible to say, of course, that this growing season was the best-ever for the genre. As far as my argument goes, honestly the weather isn’t really the main point.

What is unique about 2021 is this moment that I’ve been speaking about, for German wine and for the Kabinett specifically. All this may seem very grandiose and vague to the average consumer, but it is not at all vague for the grower. The simple truth is that many (not all) growers can now command the same amount of money with their Kabinetts as they can with any other wine; the relationship between the Prädikat and the cost of the wine has been largely shattered. This is the game-changing fact.

In other words, with vintage 2021 your average German growers have more freedom than they have ever had, to make the wine that is most appropriate for the grapes they have. This was simply not the case in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. For fame, for prestige – to compete at the very highest level for the grower – the only arena offered, truly, was the Auslese, the Auslese Gold Capsule and the rare dessert wines (the BAs and the TBAs). The oldest vines, the greatest parcels, the top vineyards – all of these grapes would have been focused on these “elite” categories, come hell or high water. Not that the Kabinett would have been an afterthought, but it just would not have been financially logical, or even viable, for growers to use their most treasured raw material in a category that had a very defined and limited price-ceiling.

And while things began to change at the turn of the century, the focus of the early 2000s (and this is where my personal involvement in this narrative begins) was almost exclusively on elevating dry Rieslings – on championing what was a forgotten, misunderstood, overlooked and undervalued category. The project of resuscitating the reputation of dry German Riesling has been successful beyond what I think most people in the German wine world could have even fathomed a decade ago. And much of this success, as nearly any grower would admit, was the willingness of the consumer to pay a higher price for dry Rieslings. When this happened, it freed the growers to use the oldest vines, the greatest parcels, the top vineyards for their dry wines – all of which previously would have been focused on the “elite” categories of Auslese, Auslese Gold Capsule and the rare dessert wines (the BAs and TBAs) – this sound familiar? It is no coincidence that the quality of the dry German Rieslings simply exploded right at this moment.

Even with vintage 2017, the last vintage that you could compare to 2021, the situation was not comparable. Yes, even five years ago the Kabinett could simply not command the price it can today. I’d love some data-wonk to look at Kabinett price-increases over the last ten years; I’d bet we’d be plotting a curve that was moving roughly with inflation for most decades. Sometime around 2017 it began to push higher and by 2018 and 2019 the trajectory turned aggressively skyward. Certainly there was in 2017, as there is now, a large audience that valued the Kabinett very highly. Five years ago I was most definitely already arguing with every critic I met about the fact that there should be a 100-point Kabinett; not because I give a **** about point scores, but because I felt the Kabinett, as a genre, deserved the respect and the space given to the “top” dessert wines.

Well, things move quickly sometimes.

Hard at rest with Auction Egon Müller

Julian Haart’s 2020 Ohligsberg Kabinett “Alte Reben” was awarded 100 points in 2021; Keller’s Schubertslay auction Kabinett, which was introduced to the world in 2019 (with vintage 2018) has commanded staggering prices getting frighteningly close to four-figures.

As a sign of how popular “the Kabinett” is becoming, the inconceivable happened for the first time with vintage 2019: Egon Müller’s auction Kabinett fetched a higher price than his auction Spätlese. The spread between the two wines wasn’t much, 20 Euros only: 241 Euro for the Kabinett and 221 Euros for the Spätlese, but still. I was watching the auction and my jaw hit the floor. The assumption that a Spätlese is more expensive than a Kabinett is a part of a pricing hierarchy more or less unquestioned for nearly 50 years. Plainly put: This assumption is no longer.

Proving that this was no fluke, for vintage 2020 the spread only grew: Egon’s auction Kabinett hammered at 322 Euros and the Spätlese at only 276 Euros. The auction Kabinett has clearly become the darling of many serious collectors who only a few years ago likely would have only focused on the Auslesen. The price for Egon’s auction Kabinett increased a whopping 61% from vintage 2018 to 2020.

And if these are the elites of the elites, and they are, there is ample evidence that this trend is working its way through the German wine landscape. The auction Kabinett of Willi Schaefer – long considered one of the most profound values in German wine – hammered at 100 Euros, becoming I believe only the second Kabinett auctioned at the Mosel VDP auction to reach the 100-Euro mark. All of this pricing is moving quickly; peoples’ jaws dropped in disbelief that a lowly “Kabinett” could get 100 Euros when Egon’s auction Kabinett reached this milestone.

In the end, the question regarding the historical quality of the 2021 Kabinetts is a red herring; it’s a false and irrelevant question. Yet the elevation of this category, the recognition that the Kabinett is in no way a “basic” or “entry-level” wine has given the growers unprecedented freedom – the laundry list of singular Kabinetts coming to market with the 2021 vintage, this is the proof of this freedom made manifest.

Obviously all markets work at their own quirky pace; simultaneously not all growers, nor all consumers (nor all importers and distributors frankly) fully realize what is happening with the Kabinett. The truth is it’ll be a curious and non-linear few years as we watch the pricing of Kabinetts, Spätlesen and Auslesen find their new equilibriums. But believe me, it will no longer be the unquestioned, moderate price increase from one Prädikat to the next. The “great” Kabinetts will simply be more expensive than the “fine” Spätlesen and Auslesen, as it should be. As with the pricing of various growers’ Clos Vougeots, the market will sniff out the quality and there will be a price to pay for that.

And while the pricing will continue to go up dramatically, for the moment, as the market processes these dramatic changes, we will likely have a window of a few years to find some simply exceptional deals.

the magic of the Feinherb

Fear not the Feinherb, the Halbtrocken, the curious Rieslings that float in this beautifully grey area, neither truly dry nor off-dry. While these wines evade our instinctual yearning to make everything binary, either a 0 or a 1, white or black, dry or not dry – the truth is always more complicated, more beautiful, more perfect and unknowable.

With vintage 2021, these wines are even more quixotic, structured, bracing and salty – in other words, they are awesome. In youth, for the next 6-12 months, they are going to be freakishly, sneakily, incredibly dry-tasting. Take, for example, Weiser-Künstler’s estate Feinherb (the wine with the owl label); this wine has around 15 grams residual sugar and 10 grams of acidity. The wine was so bracing in its original form Weiser-Künstler even super-charged this wine: it has half a Fuder of Ellergrub Spätlese blended into it, just to slightly polish some of the most extreme angles. Still, at the moment, even with 15 grams of residual sugar, the wine tastes dry. It is almost unfathomable.

Titans of New Germany: Christoph Wolber of Wasenhaus, Stefan Vetter and Jakob Tennstedt

Here’s a short list of wines to look for – we know it can be a bit confusing.

Lauer’s “Barrel X,” “Senior” and No. 4; any Ludes wine that says “Kabinett;” Seehof’s estate feinherb and “Elektrisch;” Stein’s “Weihwasser” and Himmelreich Kabinett Feinherb; the Vineyard Project 005 Saar Riesling Feinherb (made by Peter Thelen at Petershof); Weiser-Künstler’s estate Feinherb (the one mentioned above, with the owl label) and their Steffensberg “im Löwenbaum” Spätlese Feinherb, though only five cases of this are coming to the U.S. so good luck there.

All these wines may be a bit illegible and citric in youth, but give them a year in bottle, and it is my sense they will begin to unfurl and reveal simply heartbreaking midpalates of citrus and flowers, salt and mineral. These wines easily have the stuffing to develop very, very well over the next decade and probably beyond. I ache at the thought of these wines in ten years.

In other words, it is a mistake to think of these wines as “simple” and only to drink them young. For the billionaire collector who loves this style, go deep because these are serious, serious wines and they will cost you nothing – you’ll still have plenty of dough to waste on buying Twitter. More importantly, for the collector on a more meagre budget, there is a whole world of very proper and very collectible wine that will be in the $20-$25+ range – an insane value proposition made even more insane in this vintage.

Spätlesen and chicken

Let’s speak openly: It wasn’t until sometime in the late 1990s and early 2000s that Spätlesen became a dessert wine. The new ease of reaching higher ripeness levels, the influence of Robert Parker and the 100-point scale, our own seemingly insatiable love of sweetness. If all these things pushed many growers a bit too far in the first decade of this new century – and I’d include Kabinett, Spätlese and Auslese as being a bit abused – for some reason the Spätlese as a genre seemed to have suffered the most. They became almost grotesque caricatures of what they once were; folds of textural, voluptuousness where there used to be a savvy leanness, a spirited mid-palate.

The Grand Master Ha-Jo likes Chicken and Spätlesen

It’s been getting better this past decade – those that had forsaken Spätlese are warmly welcomed back: try the new “old” Spätlesen.

For vintage 2021, what I’ve tried has been spectacular; they are, as you’d expect, lighter, leaner, more elevated and linear. You can pair them with chicken; drink them with dinner. Konstantin Weiser sat there in his tasting room, with the sun pouring through the window at a fresh angle, and said quietly: “2021 was a dream for Spätlesen.”

There is however, not much of it. They are exceptional, but not plentiful. Stein made none; Weiser-Künstler made a Fuder and a half (though half, as stated, was blended into the estate feinherb) and Vollenweider only a Fuder. From both of them, we will get about 20 cases for the U.S. – same with Ludes. From Lauer we’ll get only 10 cases.

If you do see them though, reconsider the Spätlese.

“I only drink dry wines.”

It’s true that nearly all the focus of the 2021 vintage coverage has been, very much like this vintage report in fact, focused on the off-dry wines – the feinherbs and Kabinetts. This all makes sense; it’s the easy and powerful and, well, honest narrative.

With that said, I was shocked by the balance and poise of the dry wines. If you “only drink dry wines” (which is a crazy thing to do FYI), you’ll nonetheless be in very good shape in 2021 – perhaps you’ll have to be a bit more selective than normal, but there are wines out there for you. In fact, there will likely be some absolutely bonkers dry wines in 2021, as there were in 2004, 2008, etc. and so forth.

Joys of travel in the 2020’s

Remember that in many regions in Germany, the ripeness levels of the grapes were really not that far from the ripeness levels achieved in the warmer vintages like 2019 and 2020 – perhaps 90 Oechsle in 2019 and 2020 and 88 or 89 Oechsle in 2021. Off the top of my head I’d say places like the Nahe, Rheinhessen, Pfalz, Swabia and Baden have a leg up over the Mosel, Saar and Ruwer for dry wines, though I haven’t had enough dry Mosel wines yet to base this in all that much experience. Dry Rieslings also just require more time; when I was there in March tasting, many of the dry wines had only recently finished fermenting, or were just still in tank.

To some extent, the wines with a bit of residual sugar say more earlier; they are the first chapters and the dry wines are the conclusions. It is not for nothing that Keller doesn’t even release his top GGs (the Abtserde and Morstein) until the spring, after the spring, after the harvest. (Got that?)

What I do know is that in 2021, unlike say 2019 or 2020, growers had lots of perfect grapes for feinherbs and Kabinetts. To harvest a top dry wine in 2021, you had to wait. The harvests for the top dry wines took place at the end of October, after many growers had already picked a lot of their grapes, having sensed or tasted the absolute perfection of many of the grapes for Kabinetts and feinherbs. Thus, by the time mid- to late-October came around, and the grapes were perfect for dry wines, well, there likely weren’t as many grapes out there. This could also explain, to some extent, why there may be more great dry wines from the more southern regions. The Mosel, Saar and Ruwer have a stronger culture of off-dry wines, so growers there would have perhaps had an easier time making a higher-than-normal amount of such wines, while growers in the south would have felt safer making more dry wines.

However this all ends up, it would be false to paint vintage 2021 as “only” an off-dry vintage. Yes, the feinherbs and Kabinetts will be the bulk of what this vintage produced, but the dry wines, these rarities, may be among the most cutting and rewarding. Anyone who’s had a 2008 GG recently may shiver a little in anticipation. Either way, if the dry wines of 2021 turn out to be a surprising strength of the vintage, the one unquestionable fact is that they will be rare.