It might seem outlandish to present a wine you’ve likely never heard of, Emrich-Schönleber’s 1er Cru Niederberg, as a qualitative equal to the legendary Grand Crus Halenberg and Frühlingsplätzchen.

I honestly and truly do not think this comparison is outlandish, at all, but you’ll have to seek out this bottle and make up your own mind.

Either way, introducing a new wine is always a sucker’s work – especially when it comes bearing a new symbol and classification, not “GG” but “1G” or Erste Lage, the new Germanic equivalent of the 1er Cru.

Like a stranger at a party of good friends, a new bottling presents itself with, let’s say, a wide range of possibilities. Sure, the stranger could be a dynamo, the future-life-of-the-party and trusted, beloved friend. But the stranger could also be a damp fart, with all the charm of dirty shag carpet, or worse. The safest recourse, always, is to stick with what you know.

The only downside is missing something new, something great. The downside, in a way, is everything.

If one should in general avoid wading deep into German wine law and tax documents, the curious case of Niederberg is one of the rare occasions worth a bit of explanation – some context.

The Niederberg is a remarkable site lost to the historical record for over fifty years. It is perhaps a site that would be commonly mentioned in the same breath as the other great sites of Monzingen, were it not for this historical burp. One has to give credit to the Schönleber family for going through the trouble of registering a new, all but unknown name with the simple motive of correcting the historical record and bottling a wine that is truthful to the site.

For all the thrill of filing your taxes, you can read the official bureaucratic document outlining every aspect of the Niederberg vineyard here, or make yourself some coffee and get comfortable for just a touch of history.

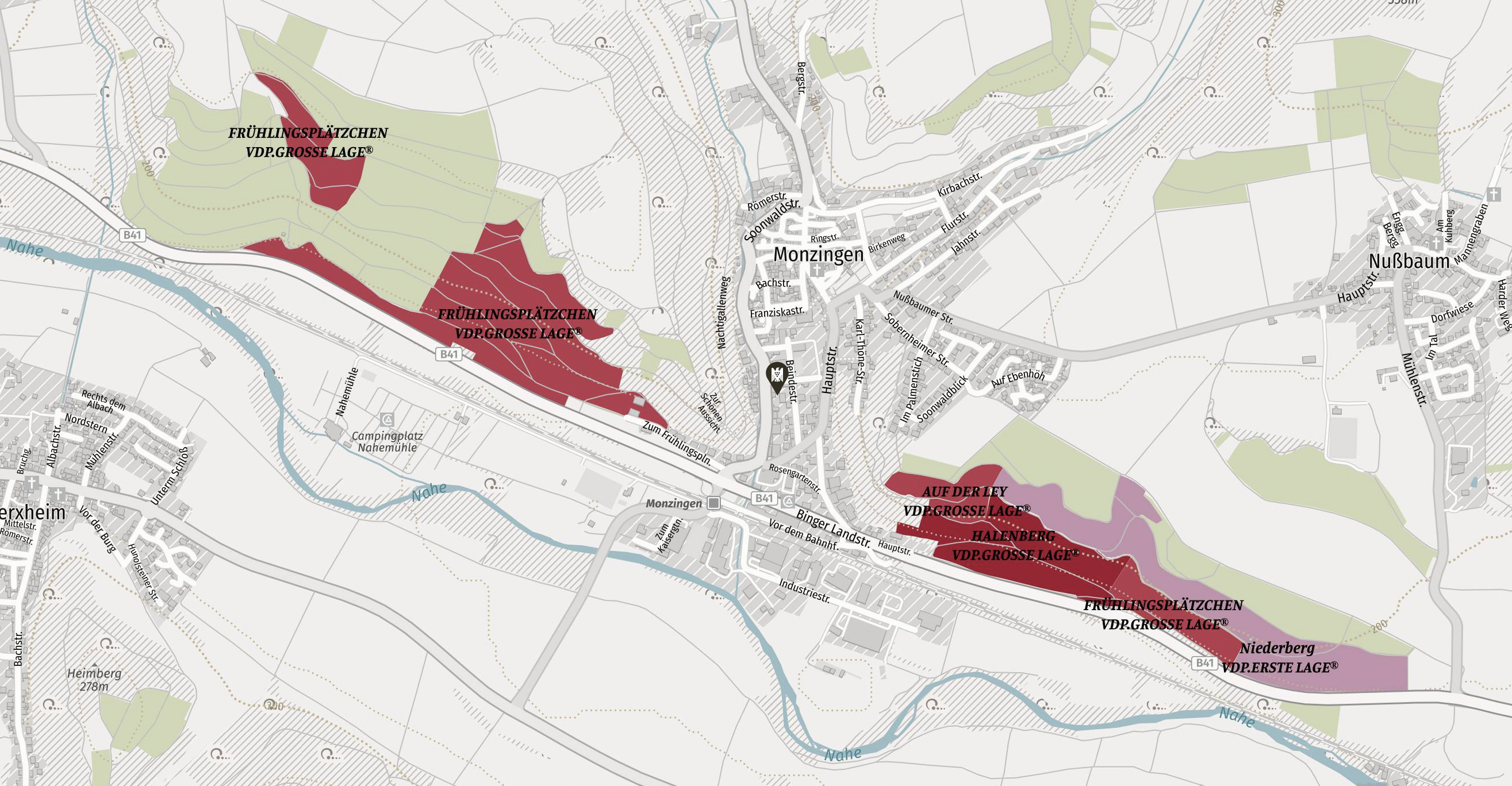

Beginning with the 1971 wine law when many vineyards were reorganized, the Frühlingsplätzchen was expanded to include not only the historical area west of Monzingen village (the left side in the map above), but also for the first time incorporated a section of vines east of the village (the right side) surrounding Auf der Ley and Halenberg, which were never historically a part of Frühlingsplätzchen. You can see this area on the above map in the lower right-hand corner, where Frühlingsplätzchen picks up east of Halenberg and where the pink outlined Niederberg is now indicated.

Beginning with the 1971 wine law when many vineyards were reorganized, the Frühlingsplätzchen was expanded to include not only the historical area west of Monzingen village (the left side in the map above), but also for the first time incorporated a section of vines east of the village (the right side) surrounding Auf der Ley and Halenberg, which were never historically a part of Frühlingsplätzchen. You can see this area on the above map in the lower right-hand corner, where Frühlingsplätzchen picks up east of Halenberg and where the pink outlined Niederberg is now indicated.

In contrast to Halenberg and Frühlingsplätzchen, the Niederberg vineyard features a unique outcropping of slate with quartzite veins, much more similar to the Halenberg’s geology — if a hundred or so million years younger — but VERY unlike Frühlingsplätzchen’s red slate which is what it was previously incorporated as.

Thus, for nearly fifty years, any producer with holdings in this area had two choices, to bottle a wine from this area as Frühlingsplätzchen while perhaps knowing that it was distinct geographically, climatically and geologically, or to declassify the fruit from this top rated site into a simple Gutswein or Ortswein without specific recognition to where this site came from within the village, such as the Schönleber’s did in 2018 with a “Monzinger NB” bottling before Niederberg was recognized, again.

Niederberg was only given name recognition in the 2019 after the Schönleber’s petitioning, using the EU’s “protected designation of Origin,” or PDOg. This new EU wine law gives growers a new agency to correct the historical record around site names, which is what the Schönleber’s did. Then, once the site name was awarded, the family petitioned the Niederberg for recognition as an Erste Lage or Premier Cru through the VDP.

Thus, beginning with 2019, a new wine in the Emrich-Schönleber stable was born.

Alas, this is an all-too common story of a bureaucracy put in place to protect the history of place names — very often seeking to unravel previous bureaucracies put in place to simplify more complicated truths in an effort to make sales easier and simpler. In Joachim Krieger’s The Mosel, Taking the Long View, he notes this push and pull of the law versus truth: “There is, in other words, both a bureaucratic and a physical reality, and the two are in consistent conflict with one another. The law blotted out the truth, and with it a unique, deep tradition, now to be found largely in old maps, books, labels, and, crucially, in both the hearts and the everyday activities of serious growers.”

And so the Niederberg existed only in the hearts of growers like the Schönleber’s, held secretly until it was possible to correct this historical record.

The thrill of this discovery, of this historical reality, is compounded by the fact that the wine is classic Emrich-Schönleber. While it’s too early to really make grand statements about the wine’s essential truth, the higher and flatter exposition of the Niederberg suggests that it may be one of the cooler sites, benefitting perhaps from the warming climate. The Niederberg is a tightly wound spring of a wine, precise and cutting. There is more citrus here compared to Halenberg; the wine feels more immediately vivid and articulate in its youth. Texturally this is just screaming for food, it has the kind of edges that grip onto whatever you are eating and won’t let go. This wine is stately and king-like in its combination of gentle silky body with commanding power in the engagingly tightening spicy finish.

Get to know the Niederberg – maybe the new life of the party?

Emrich-Schonleber Niederberg Trocken 2020 – ~$58 retail

Email orders@vomboden.com to order or for more information.