This is, more than anything else, a love story.

An unlikely and unbelievable love story between a winemaker, Ulrich “Ulli” Stein, and a tiny vineyard planted 120 years ago.

I have walked this vineyard with Ulli many times, early in the morning, later in the evening. I have seen him on more than one occasion talking to the vines.

Some are so old, that all they can muster after the cycle of a year is one miniature version of a grape bunch, the whole cluster no more than a few inches tall, the individual grapes the size of the tip of your pinkie.

Ulli will say to the vine: “Thank you old friend, for your work… now you rest.”

Every single vine has a name.

When Ulli told me casually over a dinner some years ago that one of the vines is named Stephen, I honestly felt like I was going to cry.

chapter 1.

In an unknown and overlooked village in the Mosel, just down the hill from Ulli’s 19th Century hotel/bohemian mecca, a tiny vineyard of just over 1,000 vines produces, what is to my palate (and a growing number of very serious wine dorks) one of the most astounding wines of the Mosel. (Click here for our over-enthusiastic visual schemata of where this vineyard is.)

This vineyard is, as far as anyone can tell, the second-oldest producing Riesling vineyard in the Mosel, originally planted in the year 1900.

The wine is really nothing less than a testament to what really old vines can do. It is one of the most dazzling Rieslings I’ve ever had; an uncanny combination of ripe, deep, layered, fleshy exoticism (especially in 2018) with a glossy, glycerin-rich, yet also clear and crystalline acidity.

Honestly, it doesn’t make any sense, but then again I suppose that is what transcendent wines do.

We as a company don’t really speak of this wine too much, at least in a selling context. Honestly, we just never had more than 10 to 20 cases a year to offer (for the entire U.S.) and enough people knew about the wine… well, it would just disappear.

However, as we all know, 2018 was a generous vintage. So we asked early for the largest parcel we could have, and well, we think we have enough for an offer like this. In any event, the vineyard is too special, the story too crazy, the wine too good to not talk about it.

The short story is, if you are at all serious about Riesling, then just buy some of this. The wine will set you back about $65 a bottle. Email us at orders@vomboden.com and we can help you find someone who might have a bottle.

The wine does not have a Prädikat; Ulli picks the grapes when he thinks they are ripe, and he lets them ferment as they will. For 2018, it certainly has the power of a Spätlese, yet it is only just off-dry, a feinherb with about 20 grams of RS per liter.

Now, for the long story. Sit back and make yourself a cup of coffee.

chapter 2.

Perhaps the craziest part of this story is that the vineyard is just down the street from where Ulli has been living for decades, and yet he had no idea how old the vines were, how important this little vineyard would turn out to be.

It wasn’t until the owner died and willed the vineyard’s care to Ulli, that he went in to appraise the situation. This was in 2011.

Now, old vines have a certain aesthetic. Riesling vines at least, tend not to get thick and dramatic as certain other vines do. But they begin to hollow out, over a century-plus, certain parts of the vine will die, and all sorts of bizarre holes and shapes can form. Often times, as the earth moves around them (especially on steep sites where erosion over a century can be dramatic) the roots will begin to be exposed, so the vines appear to stand on two feet, with skinny and long legs rooting down into the soil.

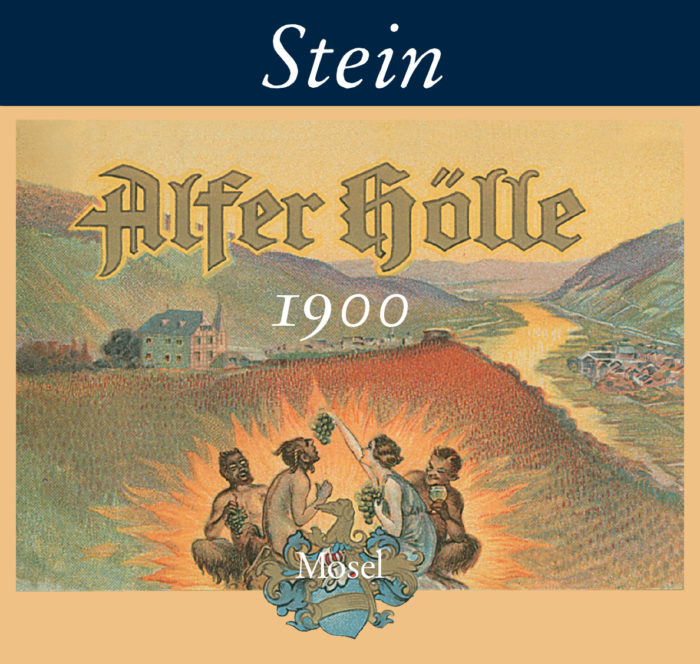

All this to say that Ulli knew immediately upon entering the vineyard, that these were old vines. He just didn’t know hold old. Ulli has his PhD in plant biology and with some friends in the research department of Geisenheim, they went on a bit of a historical search and found the planting date… as well as a copy of one of the old, original labels. You can see at the top of the drawing, the 19th century hotel (Haus Waldfrieden) that Ulli now calls home. The village is Alf, the vineyard, of course, Hell (“Hölle” in German).

Thus, we have born, with the vintage 2011, perhaps the most curious and singular wine in a collection of wines that is nothing, if not curious and singular.

The vineyard is strange, to say the least. I’ve had the opportunity to be in a number of very old vineyards, and they tend to share this commonality. Oftentimes what survives the centuries are just the edges, random fragments. And so it is with the “1900” vineyard. It is a patchwork quilt of vines, penned in by a few newer homes that must have been built after the war.

And while it’s a deeply spiritual place, it’s also very humble, even common. The gate that protects the vines from the road is old, twisted and rusted (see picture above). There really is no entrance to the vineyard. To enter, you have to climb over a low stone wall. The whole effect is to make it feel as if you’re trespassing. And in a way, you are. For most of us, these vines were planted well before our grandparents were born. This is their space; we are the intruders.

chapter 3.

The “1900” is, in a way, very non-Stein in style.

Whereas Ulli seeks a rigor and a mineral clarity that leans sometimes, shall we say, to the racier side of the spectrum (to the thrill of the acid-hounds), with the “1900” there is more freedom given to the wine. It is a more luxurious, layered, saturating wine.

The vines are pruned gently to engender a certain stability, a balance, for the vines themselves, with no thought of either increasing or decreasing the yields. The vineyard is tended as if it were a garden, the vines loved as though they were elders deserving of respect – as they are.

Thus the yields will vary considerably, from less than 500 liters to well over 1,000 liters in the most generous of vintages.

The wine ferments in neutral barrel; it is allowed to find its own balance. Thus, in any given year, the wine may be dry or off-dry, though most tend to show a delicate kiss of residual sugar. Through eight vintages, 2018 is far and away the roundest and most plush; yet, interestingly, there is still a profound freshness.

Clearly none of this was planned, but old vines are particularly stable, reacting less to extreme heat, extreme cold, extreme rainfall or drought. Some of this is just situational: older vines have deeper roots, and deeper roots don’t suck up surface water as quickly, normally finding sources of deep ground water that ebb and flow at less dramatic rates.

Thus, even in a vintage as extreme as 2018, one of the warmest vintages on record, there is a cooling, deep mineral to this wine. A cool, stony core, unwavering. It somehow makes all this opulence feel contained, even compact.

epilogue

This, you may have gathered, is a profoundly important wine for us – a profoundly loved and personal wine for us. It is a wine I buy for myself, religiously, every year.

It is not a famous vineyard, it is not a “GG” – there are no obvious superlatives. There is only history, only the miraculous discovery of something beautiful, something delicious, hidden in plain sight.

Email us at orders@vomboden.com if you’d like help finding a bottle of two.

Thank you for reading and for all your support.