Stefan Vetter is f-ing punk rock.

In other words, Stefan has done nothing that has even the slightest commercial logic to it.

His old friend and brother-in-law Andreas Adam (of the celebrated Mosel estate A.J. Adam) must shake his head, watching Stefan, like a wild hermit, run himself up into the terraced vineyards of Franconia (see below) pursuing a most unlikely hero, Sylvaner.

Yet from a scant few hectares of old vines, working only terraced vineyards completely by hand, Stefan is reimagining what Sylvaner can be – what the wines of Franconia can be.

Yet from a scant few hectares of old vines, working only terraced vineyards completely by hand, Stefan is reimagining what Sylvaner can be – what the wines of Franconia can be.

Sylvaner isn’t a particularly aromatic grape. At best it’s famous for its textural element, its rustic, saline, crunchy acidity. The structure. Yet the wines that old-vine Sylvaner produces, when farmed well, are a profound looking glass into the soil and reflect, with astonishing sensitivity, the changes of terroir. Truly great Sylvaner, Stefan Vetter’s Sylvaners, deserve the more rarified context of Chardonnay (the wines of Chablis and the Chardonnays of the Jura seem especially appropriate here).

These wines are a shocking, brilliant, revelation.

Unlike the dramatic and steep slopes on the Mosel, the feeling in Vetter’s vineyards is more rustic and pastoral. The landscape is more bucolic, with ancient, crumbling terraces nestled quietly and subtly in the hills, surrounded by all manner of wild growth – trees, bushes, orchards, etc. Vines grow here over a base of sandstone and limestone. It’s like the Mosel collided with the Pfalz or Baden and spat out Franken.

It’s no coincidence that Stefan Vetter would be drawn to vineyards like these; his temperament is a perfect match; slow and careful, with a methodical attention to detail, and not shying away from hard work. He seems physically drawn to these old terraced sites; he wants to work them and he wants to save them. He feels the greatness and the history, and he’s willing to do the hard work to let it show through in the wine.

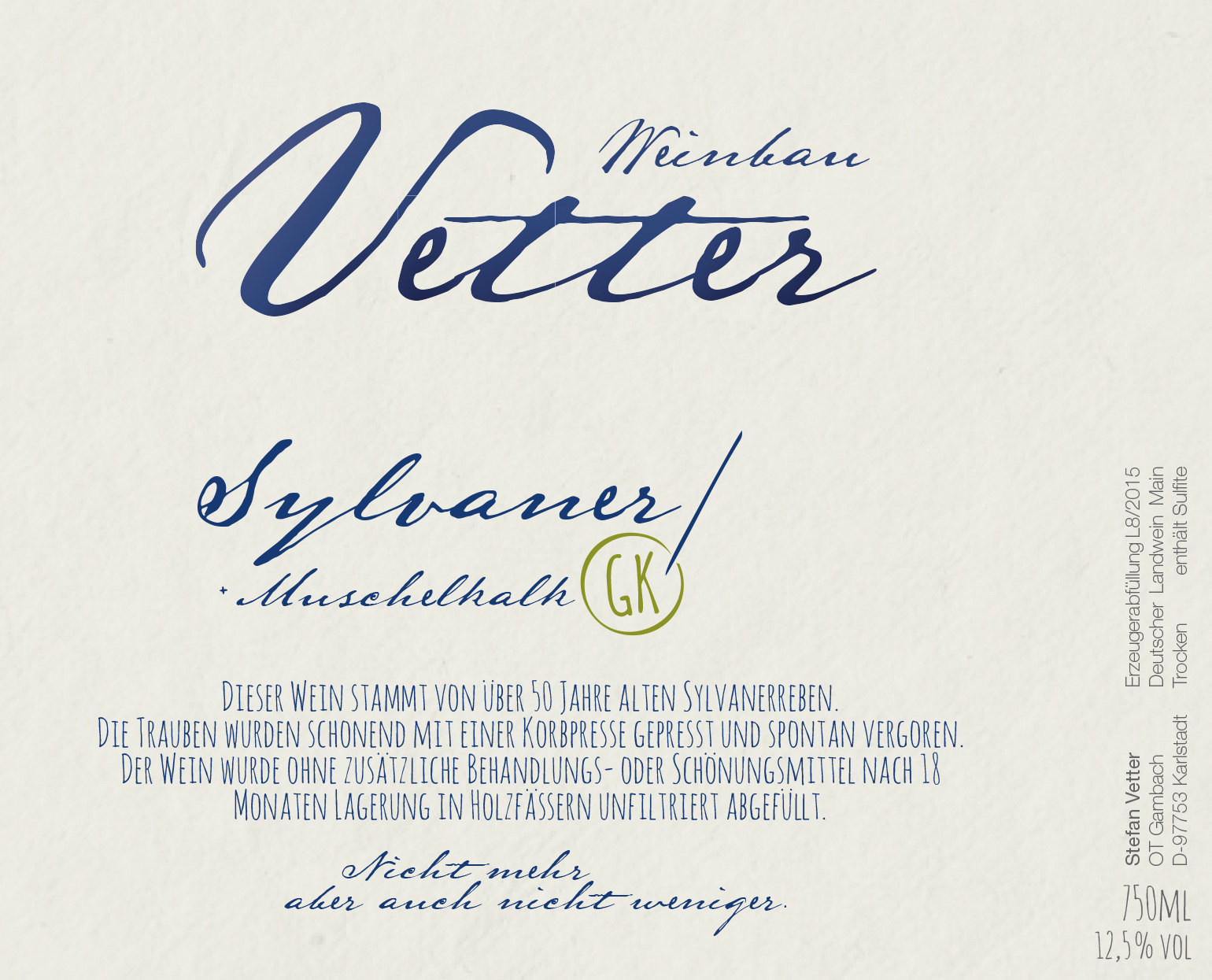

Stefan is at the forefront of the natural wine movement in Germany. As such, he farms both organically and biodynamically, as would be expected. As he works only old vines, only in steep, terraced sites and everything is done by hand. Pressing is done gently with either an old screw press or a basket press and can take four to six hours. For the most part, Stefan picks earlier, looking for ripe, clean grapes with higher acidities.The juice may see a short bit of skin contact, but for the most part it is just moved directly into old barrels – or one of the few newer 300 or 600-liter barrels Stefan has acquired directly from Stockinger. During the élevage, the wines are topped off, but that’s about it.The wines are bottled without filtering and with a minuscule addition of sulfur for stability.

Stefan is at the forefront of the natural wine movement in Germany. As such, he farms both organically and biodynamically, as would be expected. As he works only old vines, only in steep, terraced sites and everything is done by hand. Pressing is done gently with either an old screw press or a basket press and can take four to six hours. For the most part, Stefan picks earlier, looking for ripe, clean grapes with higher acidities.The juice may see a short bit of skin contact, but for the most part it is just moved directly into old barrels – or one of the few newer 300 or 600-liter barrels Stefan has acquired directly from Stockinger. During the élevage, the wines are topped off, but that’s about it.The wines are bottled without filtering and with a minuscule addition of sulfur for stability.

It is hard to contextualize what Stefan is doing within the history of Franken. As with the Rheingau, the wines here were once among the most celebrated in Germany. Würzburg, the region’s largest city, became very wealthy from the wine trade and many giant old domains still exist, churning out mostly nondescript, wine-like creations that do no justice to the estates, the vineyards and the region as a whole.

Stefan is changing this, a few old vines at a time.

(Psssssst… did we mention Stefan also makes a cider? Delicious, bubbly, all-natural, sulfur-free cider from five indigenous Franconian apple varieties, all with amazing names like Winterrambur.)